I survived because we were a small family. Families with more members went to Poland

Download image

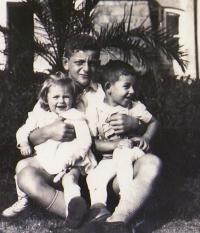

Igor Eli Stahl was born in 1934 in Slovakia in Bánovce nad Bebravou. His father owned a freight company, he belonged to a very renowned and respected Jewish family in Bánovce. In 1942 - in the era of the Slovak state - he and his mother were placed into a forced labor camp in Nováky, where they stayed until the beginning of the Slovak national uprising. His father was deported to the Lublin ghetto, where he died. The last war winter, he and his mother had to hide with the partisans in the mountains near Donovaly. After the war, he became the sole owner of all the property of his murdered relatives - up to 1948 he thus became one of the wealthiest people in Bánovce. In February 1949 he left Czechoslovakia and settled in Israel, since the fifties, he lives in the Kibbutz Kfar Masaryk. In the Israeli-Palestinian wars, he served as a tank-mechanic. He has two sons, his wife died in a car accident three years ago.