They had all their lines rehearsed, but no one anticipated that there would be death sentences

Download image

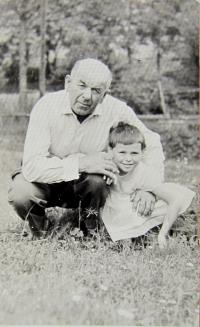

Anděla Černá, born Andela Nerovalova, was born on 22 June 1935 in Vranín near Moravské Budějovice. Her parents owned a farm in the middle of this little village with twelve acres of fields. Her father, Jan Nevoral, was imprisoned in Jihlava for eight months during the war for the illegal milling of flour. Her father was strongly opposed to the events of February 1948, when the Communist Party took over all power in the country and, among other things, began using repressive means to enforce the collectivisation of agriculture and the related founding of united agricultural cooperatives (UAC). At the first opportunity Jan Nevoral joined a resistance group formed around Gustav Smetana, which tried to work towards the overthrow of the regime. On 17 June 1951 he was arrested by State Security, and on 19 and 21 May 1952 he and another eleven men from the group around Gustav Smetana were placed on a public trial in Moravské Budějovice. This was one of fifteen trials undertaken in the context of the Babice Case, in which 107 people were given lengthy prison sentences and 11 were sent to the gallows. Two of the death sentences were in Gustav Smetana’s group, Jan Nevoral was sentenced to twenty-three years of prison and the loss of all his property. His daughter Anděla had to give up her grammar school studies, and in the end, on 7 November 1952, she and her mother and brother were deported to Hynčice pod Sušinou, more than 260 kilometres away in the border region of north western Moravia, on the eastern slopes of the Králický Sněžník massif. Her father was released by a presidential amnesty in 1962. Until her retirement Anděla Černá worked at the Staré Město State Farm. She now lives in Šumperk.