By 1953, they weren’t beating us anymore. At least, where I was, they were no longer beating people.

Download image

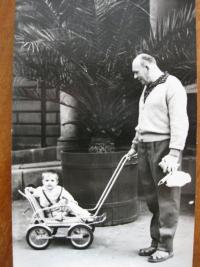

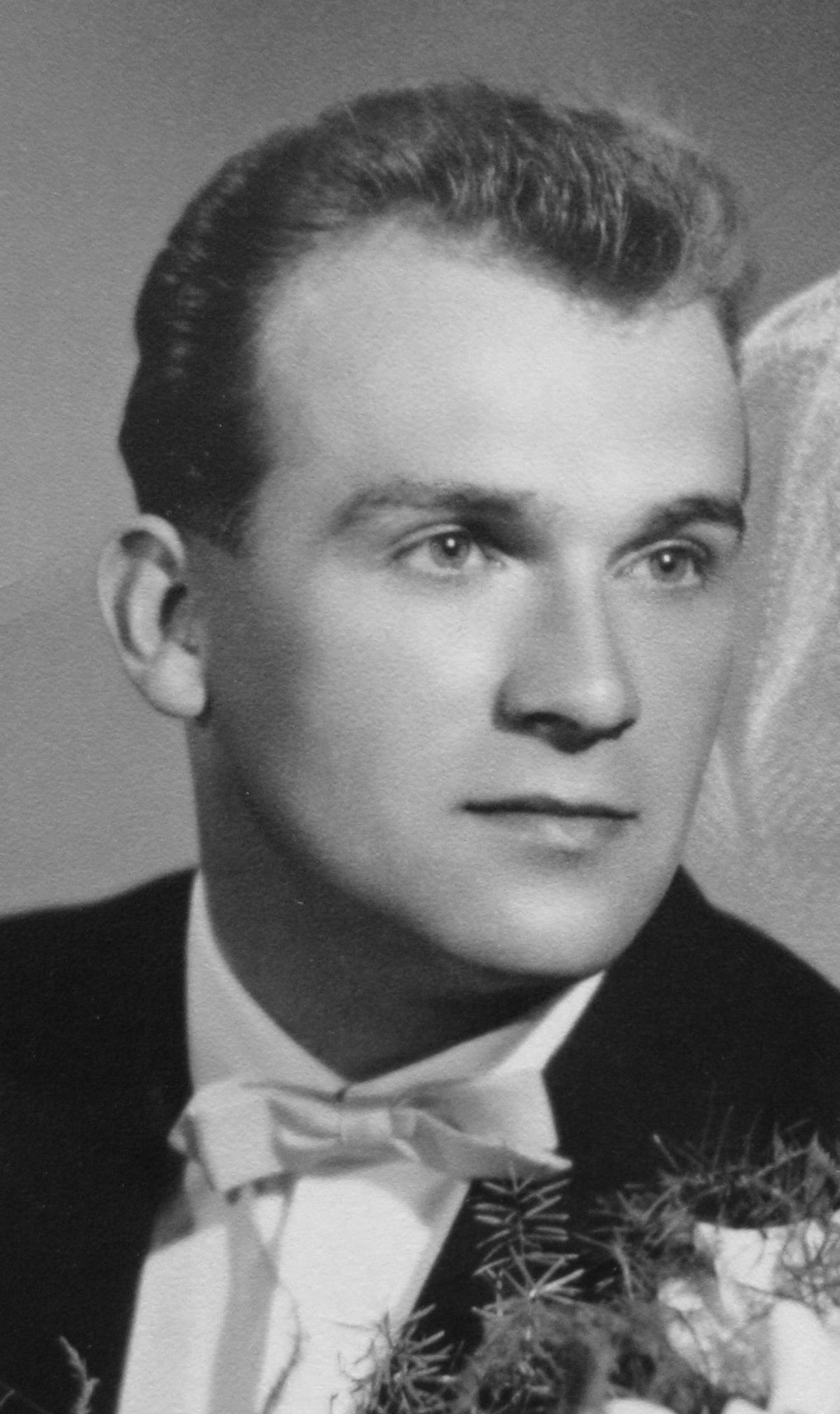

Josef Černohorský was born on April 11th, 1935. He spent his childhood years in Domažlice. His father, lieutenant colonel Josef Černohorský, was a Czechoslovak army officer. During the war his father was imprisoned in the Flossenbürg concentration camp in relation to the Jan Smudek case. After the war the family moved to Pilsen, where Josef’s father worked at the army command. His father was arrested in 1950 and sentenced to 23 years of imprisonment for alleged anti-state activity (the group Josef Kučera and comp.). He was held in the Leopoldov prison and released through amnesty in 1960. Josef Černohorský attended a grammar school, which unfortunately closed down in 1948. He transferred to vocational training for electro-technicians in the Škoda factory in Pilsen, which he completed in 1952 and then began working in the factory. In June 1953 he was arrested for alleged participation in the Pilsen uprising and he was sentenced to a year of imprisonment. He was imprisoned in the camp Barbora in the Jáchymov region, where uranium ore was mined, and he worked there as a trammer. After his release he was working in the Construction Company of the City of Pilsen full time until it closed down in 1990. While working, Josef took evening classes at a secondary industrial school. In 1990 he was rehabilitated and he also founded a plumbing business with his colleagues, from which he then retired. He is a member of the Confederation of Political Prisoners and till 2008 he also served as the chairman of its Pilsen chapter.