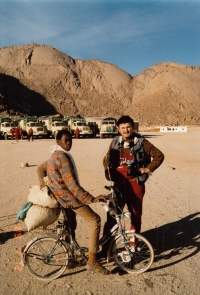

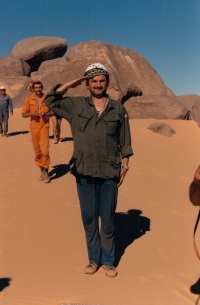

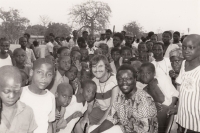

After emigrating, I experienced how people help refugees. That’s why, as a volunteer of the Order of St. Lazarus, I liked to help the sick

Download image

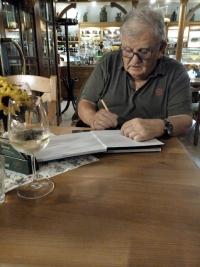

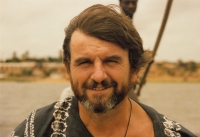

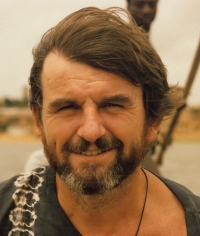

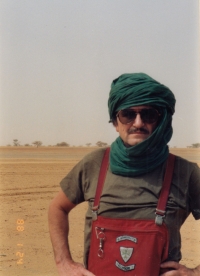

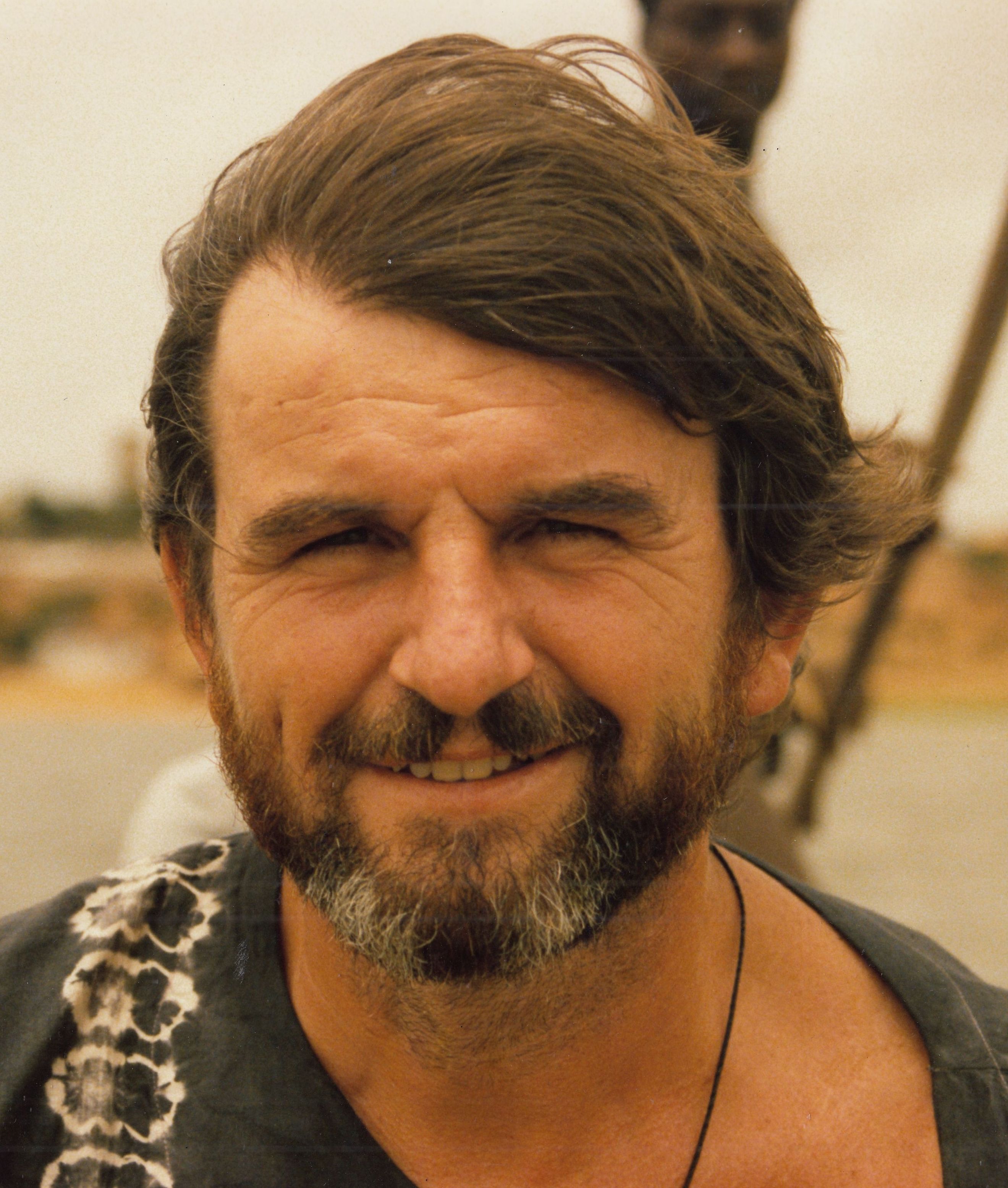

Václav Chabr was born on 13 July 1943 in Radobyčice near Pilsen. His father František Chabr came from Plzeň, worked in Škoda factory, was a scout and a tramp. His mother Marie Chabrová, née Součková came from Podmokel, and came to Pilsen during the Heydrichiad. The family experienced the bombing of the Škoda factory, and father found them covered in rubble. One of the liberating soldiers in Pilsen was mother’s relative Bohumil Souček from Chicago. Václav Chabr graduated from the Julius Fucik Real Gymnasium in Pilsen. From 1956 he was a member of the Oregon tramp settlement. His father, who was a member of the Communist Party, told him about tramping and scouting. He had no ideological influence on his son, unlike his anti-communist friends. Václav Chabr graduated from an industrial engineering school, and in his first year he made his first unsuccessful attempt to escape to the West. A second unsuccessful attempt at emigration followed around 1960. He was sentenced to 16 months’ imprisonment without parole for illegal residence abroad. The trial took place in Spišská Sobota. After the amnesty his sentence was changed to a suspended one. After completing his compulsory military service in Kežmarok, Slovakia, in 1964, he continued to work at Škoda as a married man. On 8 May 1968 he finally emigrated successfully to Germany. His wife and son did not come to see him, her parents talked her out of it, and she died soon afterwards. In Germany he graduated from university, founded a company and married for the second time. With his wife, also an emigrant, he raised a daughter and a son. As a volunteer member of the Order of St. Lazarus, he provided aid for leprosy patients in Africa. In 1990, after 22 years, he returned to his native country. He married for the third time to Svetluša Tomšovicová, who worked as a nurse. From 1992 he ran the St. Moritz guesthouse in Železná Ruda, published the Železná Ruda Newsletter, and was chairman of the Železná Ruda Club. He began to devote himself fully to professional photography. At the time of filming (2023) he lived with his wife in Železná Ruda.