A person should try to uphold the basic values of life at all cost

Download image

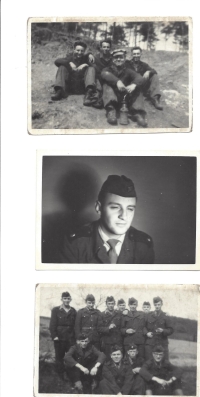

Lubor Chvalovský’s fate was already partly predestined by his family background. He was born on 5 October 1933 in Prague, the second child of Josef Chvalovský and Emilie Chvalovská, née Goliathová. His father was a legionary who was a high-ranking officer of the Czechoslovak Army during the First Republic, his mother came from the family of the merchant and successful left-wing politician Otto Goliath, who together with his son JUDr. Karel Goliath was among the prominent functionaries of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia in the first half of the twentieth century. The whole family was gravely impacted first by the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia, during which time Lubor and his sister lived with relatives. His father was forced into emigration during World War II, where he joined the anti-Nazi resistance. In 1944, among other things, he took part in the siege of the French port of Dunkirk as the deputy commander of the Czechoslovak Independent Armoured Brigade. Lubor’s mother Emilie was imprisoned throughout the war and held first at a camp in Svatobořice, later in the Small Fortress in Terezín. After the war the family moved to Hodonín, where Lubor’s father took up command of the local garrison and whence he was forced to flee Czechoslovakia a second time under dramatic circumstances in April 1949. The rest of the family wanted to follow him, and so in autumn 1949 they attempted an illegal border crossing near the village of Nemanice. Lubor’s sister Naďa succeeded in crossing over, but Lubor and his mother were caught and arrested by the border guards. The adolescent Lubor was released after two months, his mother was sentenced to six years of high-security prison for sedition. Lubor was not allowed to continue his studies for political reasons, he started earning a living as a worker in a brick factory. In the years 1953 to 1955 he underwent compulsory military training - he was drafted directly into the Auxiliary Engineering Corps (forced labour). He served at the mine Antonín Zápotocký in Kladno. In the 1950s Lubor’s mother Emilie was arrested and sent to prison again, Lubor was also arrested by State Security. Both of them were interrogated in Uherské Hradiště because of the activities of Josef Chvalovský and his alleged sedition. Lubor was sentenced to two years of prison. He was released prematurely by an amnesty. His mother was given a twelve-year sentence, she was released on probation in 1959. After his military service Lubor returned to Prague and continued to be employed in manual professions. He later found a job at Čedok (a nationwide travel agency), where he remained in various positions until his retirement. In the early 1960s he managed to establish written contact with his father and sister, in 1969 they met together after twenty years in Houston in America. During the normalisation they managed to maintain at least some kind of mutual relationship. His sister Naďa settled down permanently in the USA, but Lubor remains in close touch with her to this day. After 1989 Lubor Chvalovský and his family gradually retrieved their property in restitution, and his father Lt. Col. Josef Chvalovský was fully rehabilitated by both civil and military courts.