I need to do everything for my children. And teach them to be diligent and honest.

Download image

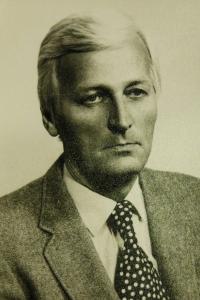

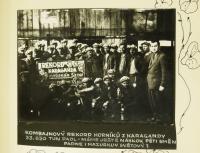

Jaroslav Čihař was born in a Czech-Slovak family. His mother was a Slovak from Košice and his father was a Czech. He was born on April 27, 1935. His father was a tradesman who owned a small forwarding company. At the end of the war he was sent to Germany to do forced labour. He was driving a truck and clearing away debris in Nuremberg which was destroyed by the bombing. In May 1945, Jaroslav Čihař witnessed the liberation of Pilsen by the US Army and the welcome given to General Patton. He also remembers the departures of German prisoners of war and the arrest of Karl Hermann Frank in Rokycany. In 1950 he took part in the so-called Lány campaign. Recruiters from coal mines were recruiting boys from all over Czechoslovakia in the Lány chateau in the presence of president Klement Gottwald. Jaroslav began studying a vocational school affiliated with the Dukla mine in Dolní Suchá in the Karviná region and in 1953 he worked his first shift underground. In July 1961 a fire spread in the Dukla mine and 108 miners perished. After the tragedy, Jaroslav helped with clearing works in the mine and he witnessed the recovering of the dead bodies. In 1966 he became a member of the Communist Party, but after the purges which followed after the occupation of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact armies he was expelled from the Party. He worked in the Dukla mine until 1990 when he retired. Since that time he has been dealing with the mining history in the Karviná region. He co-authored a book about the tragedy in the Dukla mine as well as a permanent exhibition on mining in the cultural centre in Havířov.