He saw both horror and joy behind the windows of Liaz when he brought the striking students there

Download image

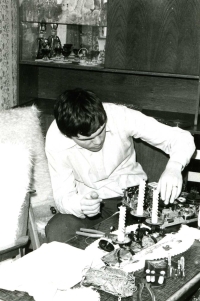

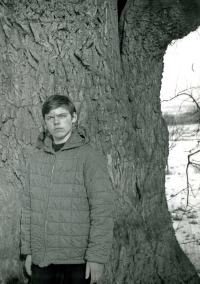

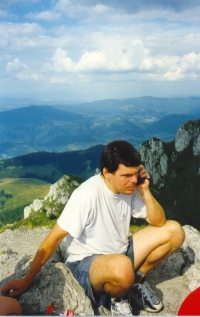

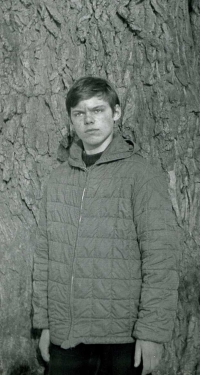

Dalibor Dědek was born on 21 June 1957 in Jičín. He lived with his parents in Radvánovice. Since childhood he was interested in electrical engineering. His grandmother told him about her experiences from the First and Second World War, which he recorded on a reel-to-reel tape recorder in the late 1970s. At the age of 11, he experienced the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact troops. His parents took him from Radvánovice to a safer place in Karlovice to his maternal grandfather. But grandfather was a diehard communist and welcomed the Warsaw Pact occupation of Czechoslovakia. There were calls in the village to hang him. The parents preferred to take the children back to Radvánovice. The witness´s father appeared in a photo of people in a factory protesting against the occupation. The family later faced problems because of this and Dalibor Dědek was not allowed to apply for secondary school studies. He trained as an electrician, later graduated from a secondary technical school and was admitted to the Czech Technical University (ČVUT). In his first year of studies he got married and had a child with his wife Lenka. He finished the university studies and started his military service at a special small unit in Prague – Kbely. There he came into contact with top secret documents. The soldiers were investigated by members of Military Counterintelligence (VKR) because of these documents, and the witness spent a night in a cell in Ruzyně prison. Military Counterintelligence made him its collaborator without him knowing it. He signed an agreement to keep VKR informed of developments in the case involving top secret documents. But he never came in touch with VKR again. The VKR file caused him trouble in the period around 2017, when he briefly got involved in politics. During the Velvet Revolution, he was working at the state-owned company Liaz Jablonec as an expert in microelectronics. He brought students into the factory, who persuaded employees to support the general strike on 27 November 1989. After 1990, he started his own business and became the owner of Jablotron, a security technology company, which he and his colleagues led to a multi-billion annual turnover. He was behind many charity projects, and after the Russian army invaded Ukraine in February 2022, he joined a fundraising campaign to buy weapons and other equipment for the Ukrainian army. He and his wife Lenka had two children of their own, a daughter and a son. In 2022, he was living in Bzí in the Jablonec region. He was living with his girlfriend taking care of her two young daughters.