Just like that, the communists had us moved to a rotten shack

Download image

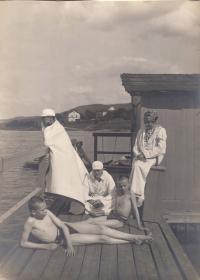

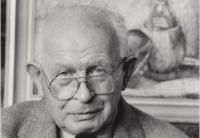

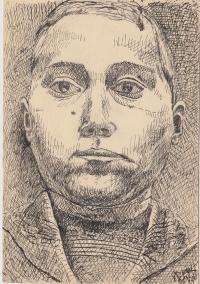

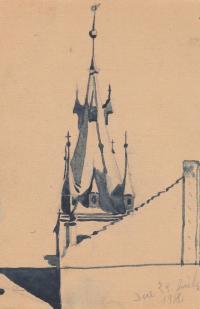

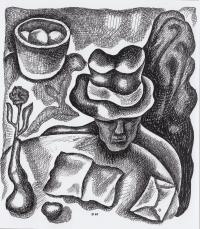

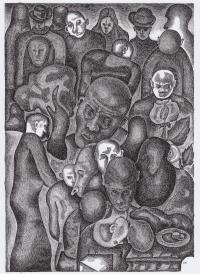

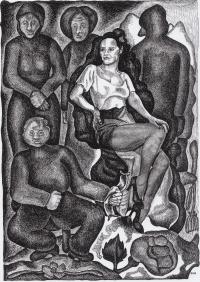

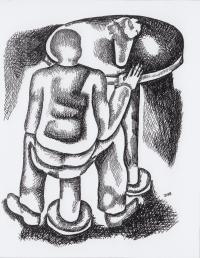

Jiří Degl was born on 17 August 1944 in Pilsen in the family of Vilém Degl and his wife Aloisie. He grew up together with his older brother Petr. Before the war, his father was a judge in Varnsdorf and Litoměřice; since the beginning of the war, he was working in Pilsen. He was expected to join the Constitutional Court in Prague in 1948. However, following the Communist coup in February of the same year, this was out of the question. Since he refused to take part in the politically motivated trials, the Communist regime gradually relegated him. Eventually, he was forced to leave his profession and take the job of a blue collar worker in the car manufacturing company Škoda. In 1953, following the monetary reform and the uprising in Pilsen - which none of the family members even took part in - the family was evicted from their apartment. They were placed into one moldy room in the Mokrouše village, where they lived in terrible conditions without access to running water and other utilities for four years, until the doctors from the health inspection intervened. The children were suffering from chronic fevers and other health issues. In 1957, the family was allowed to return to better conditions to Pilsen. Jiří Degl completed vocational training to become a locksmith, after which he graduated from a technical school of mechanical engineering. Between 1967 and 1969, he undertook military service in Klatovy. He wanted to apply for an arts school in Prague but this was not possible. He diligently attended arts courses at a popular school of arts, and also received advice from his uncle, the academic painter Theodor Pchálek. He went through several professions but his main interest was in painting with which he spent all of his free time. After 1967, he was one of the founding members of the arts group Intensit with which he was exhibiting in many Czech cities up until mid-1970s when they were banned. Following the Velvet Revolution in 1989, they started exhibiting again. With his works, Jiří took part in several important projects at the European level. Due to his life being heavily impacted by the terrifying experience from Mokrouše, he was neither politically active nor did he establish a family of his own.