You speak Romani one more time and you will know what a children’s home is

Download image

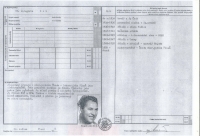

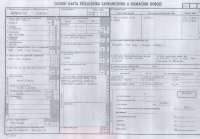

Růžena Ďorďová was born as Růžena Kotlárová on 17 July 1964 in Litoměřice. Her father, Ľudovít Kotlár, came from a family of nomadic Roma craftsmen from eastern Slovakia, her mother, Alžběta, was orphaned as a child and raised on municipal expenses. Her grandparents and parents moved to Bohemia in the early 1950s. Růžena grew up in the village of Straškov in Litoměřice region. Her father soon died and her mother raised her seven children alone. At the beginning of elementary school, Růžena and her sister Eva were illegally removed from the family and placed in an orphanage in Krupka near Teplice, where they spent two years. Their mother, although she herself could not read or write, hired a lawyer and sought in court to have them returned and to punish the persons responsible for their removal. In 1975 she moved with her children to a housing estate in Roudnice nad Labem. After finishing primary school, the witness apprenticed as a knitter at Elite Varnsdorf. She wanted to continue her studies at the secondary school of economics, but her mother did not agree. Therefore, she worked at Elite Varnsdorf until the 1990s, where she also met her husband, Vladimír Ďorď. Her son Patrik was born in 1989. In the 1990s, the factory went bankrupt and Růžena Ďorďová understood that as a Romani woman she faced racial discrimination in the labour market that was hard to overcome. When she applied for a job at a factory, her employer turned her down, citing her Romani origin as the reason. However, she took a retraining course through the employment office and became a field worker in social services in the Šluknov region. She now works for the St. Terezie Asylum House in Karlín in Prague and for the Domov na půl cesty Maják for children leaving children’s homes and diagnostic institutions. She also founded the Schola Fidentiae - Škola s(ebe)vědomí, which she handed over to Tereza Štěpková in 2022.