Don’t tell anyone, boys.

Download image

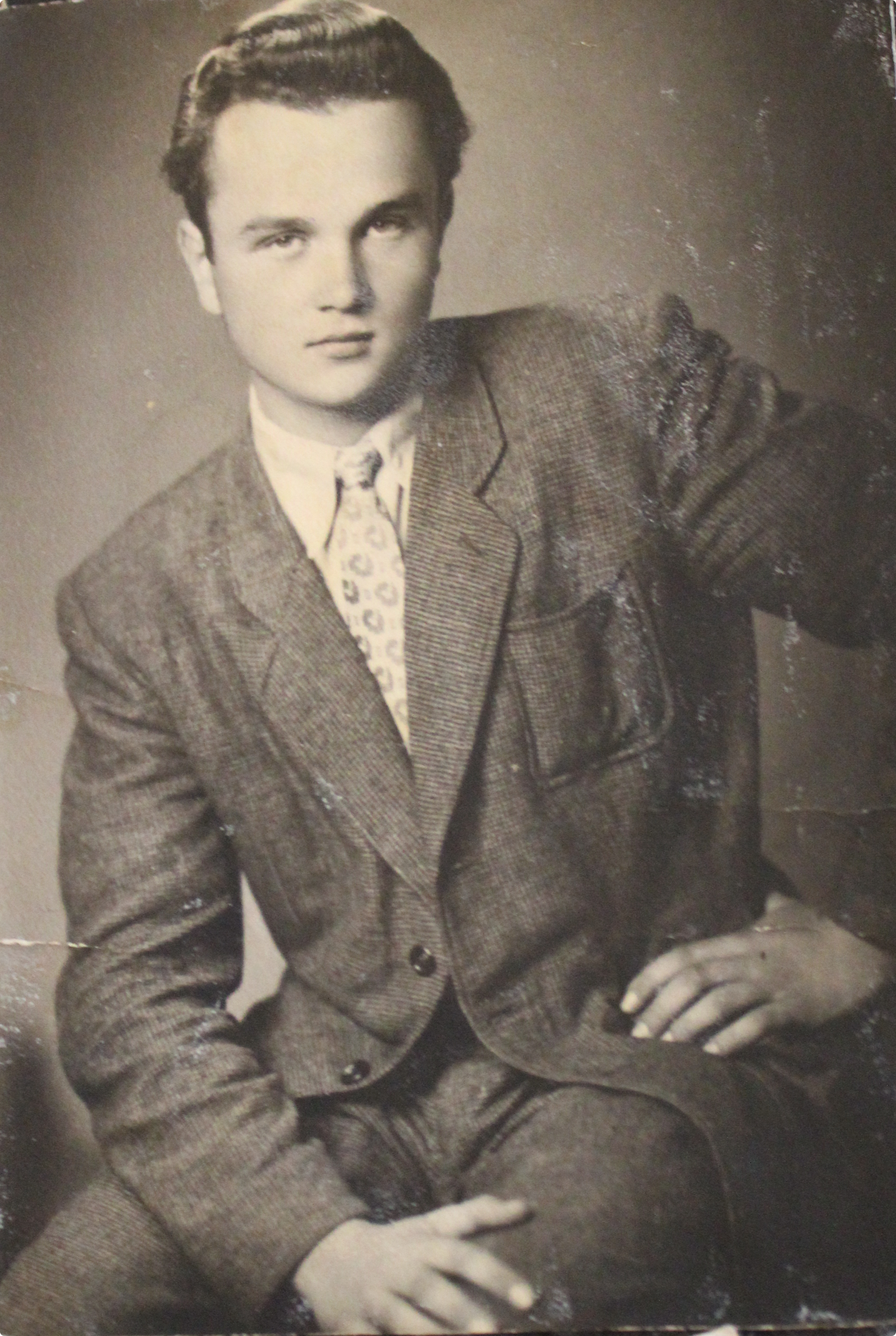

Alois Dostál was born in Hradec Králové on 20 November 1932 to Marie Dostálová, née Šafaříková (*1907) and baker Alois Dostál Sr. (*1908). One year later, the family moved from Hradec to Němčice, a small village near Kolín, where the father started his own bakery. Alois Dostál and his two younger siblings, Marie and Josef, spent most of their childhood in wartime, whereas the youngest sister Jaroslava was born three years after it in 1948. During the war years, the family was protected from hardships mainly by the father’s hard work in the bakery; the Dostáls always baked at home, and so Alois Dostál Jr. got a baker training too after the war. When his father lost his bakery in the 1950s, however, he opted to become a truck driver for the Ministry of the Interior warehouse and laundry in Kolín after his military service. He married Jaroslava Nováková, daughter Marcela was born in 1957, and he started working as a garage foreman in the warehouse. From 1962 to 1985 he was employed in the paper mills in Štětí. After his first wife died, he married Marie Veselá in 1989, but was widowed again in 2015. In the summer of 2024, he was repairing small appliances in his apartment in Kolín, occasionally going to vintage car shows with friends.