As a child of a kulak, I had no choice. Mining wasn’t that bad at the end

Download image

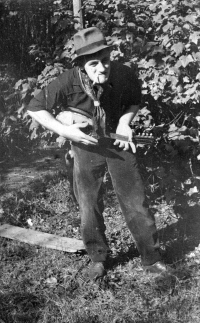

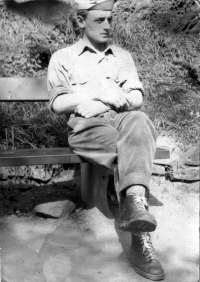

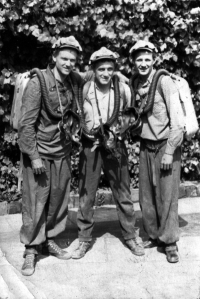

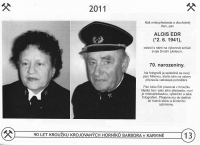

Alois Edr was born on the 2nd of June in 1941 in Zruč nad Sázavou in Central Bohemia. His parents were farmers, they owned around eighteen hectares of fields, two smaller pieces of forest, some meadows, eight cows and two horses. His father, Alois Edr the Elder, died of heart attack in 1950. During the collectivisation in the 1950’s, the family property was taken over by the State Farm. Alois’ mother started to work in a factory. Alois wanted to study at a construction trade school but as a child from the so-called kulak family, he did not get a credential. He apprenticed as a miner in Karviná and he settled there. For thirty years, he worked as a mine rescuer. He worked during many tragic event in the Ostrava-Karviná mining area. In 2022, he lived in Karviná and he was an active member of miners’ folklore group, Barbora.