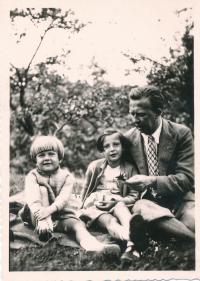

“I wanted you to become a Sokol girl - you know what that means”

Download image

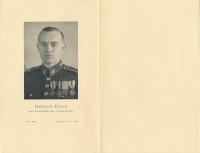

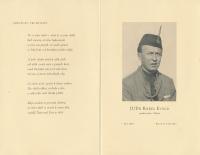

Dagmar Evaldová was born on the 31st of March, 1928. Both of her parents were keen members of the Sokol movement. Her father, a judge by profession, took part in the anti-Nazi resistance during World War II. He was active in the illegal Sokol organization Jindra but was arrested and in 1943 he was executed. His older brother faced an identical fate. Dagmar was sent to do forced labor in an arms factory in Vlašim. After the end of the war she enthusiastically participated in Sokol’s restoration. Following its ban by the communist regime, she worked in several factories because she wasn’t allowed to study. Later, she got a job as a caretaker of blind children and at the same time participated in a project called SOS Children’s Villages. She remained active in the field of blind children’s education up until retirement. After the Velvet Revolution she was one of the main figures participating in Sokol’s renewal. She died on April 25, 2022.