I didn’t want to be sober because the sobriety hurt me

Download image

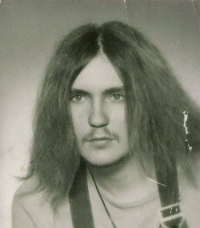

Ladislav Fabián was born on March 24, 1967 in a working class family in Havířov. After primary school, he started studying locksmith and then mining apprentice school, but he did not finish any of the schools, because he fell into drug addiction in the community of Havířov Máničky (young people with long hair, typically men, in Czechoslovakia through the 1960s and 1970s). He was experimenting with drugs (codeine) since the age of fourteen, and was addicted since the age of fifteen. During the 1980s, he was imprisoned three times and hospitalized five times in psychiatry. He felt firsthand that the interest of the totalitarian regime was to shut down and hide drug users from the public, not to cure them. He himself started successful voluntary treatment in 1993. In 1997 he started working in the therapeutic community in Čeladná as a guide for clients who want to get rid of addiction. He gradually finished high school and university and became a qualified social worker. He has been working at the Renarkon Aftercare Center for 11 years and runs the Alumni Club, which brings together people who have been addicted to drugs.