There was a hunger for information, we were substituting independent television

Download image

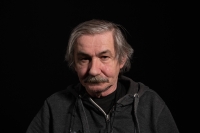

Přemysl Fialka was born in Prague on 3 June 1951. His father Přemysl was imprisoned in the 1950s for his activities in the anti-communist resistance. He worked in the uranium mines in the Jáchymov region. Přemysl Fialka liked photography from childhood and trained as a fine mechanic. After 1970 he started working at Post Office 120. He then worked briefly at Czechoslovak Television and later in hospital boiler rooms as a technician and heating engineer. Through his contacts, he joined Czechoslovak dissidents and filmed them for international distribution from the 1980s on. He married Markéta Němečková and co-founded the Original Videojournal in 1986. At that time he also signed Charter 77. With Andrej Krob and Michal Hýbek, he filmed protests in the late 1980s, interviews with dissidents, their speeches, unauthorised exhibitions and other events. During the revolutionary days he helped with filming at the Činoherní klub where the Civic Forum was being formed. After the Revolution, he accompanied his wife Marketa Fialková, who became ambassador to Poland. In the 1990s, he photographed for Lidové noviny, and since 2008 he has worked for the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes. In 2022 he lived in Prague.