The Nazis classified us, Silesians, as third-rate Germans and sent us to war

Download image

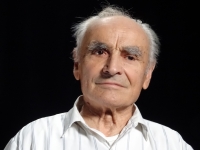

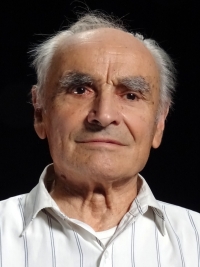

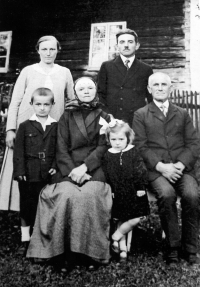

Karel Fiedor was born on September 7, 1928 in an evangelical family in Dolní Žukov near Český Těšín in Czechoslovakia. His father worked as a carpenter and with his wife took care of the farm. After the Polish annexation of Těšín Silesia in 1938, they became citizens of Poland. After the outbreak of World War II, the region was annexed by Nazi Germany. His parents claimed Silesian nationality and spoke Silesian dialect. During the Germanization operation “German Volksliste”, the occupation authorities classified them as third-rate Germans, who were given German nationality for a trial period. His father was recruited into the Wehrmacht in 1943 and sent to the Russian front. The witness had to join the German army at the age of sixteen in the spring of 1945. They were heading for Berlin, which had been taken over by the Soviets in the meantime. He and thousands of other soldiers surrendered to American troops at the Elbe River, but eventually were taken up captive by the Red Army. He spent three months in a prison camp in Brandenburg. In the end he was released and managed to get home safe and sound. The family resisted forced collectivization for several years. Karel trained as a carpenter and later worked in the Třinec Ironworks. He worked as an electrical maintenance foreman in the rolling mill. In the 1950s he moved to Třinec-Lyžbice.