The deportation passed them by, but as Germans, they lived on the edge of poverty

Download image

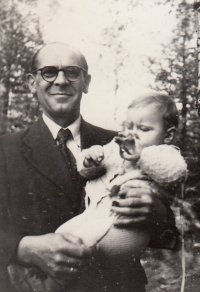

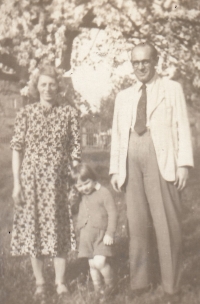

Bruno Fischer was born on 30 August 1947 in Cheb into a German family. His father was hiding from total deployment at the end of the Second World War. After World War II, his parents did not have to be deported; his father was needed as a specialist in the chemical and metallurgical industries. From 1950, they lived in Habartov, where more Sudeten Germans stayed and worked in the mines. Because of their German origin, the parents’ work opportunities worsened, and the family lived on the edge of poverty. In the 1960s, they wanted to move to the West, but they did not have the money. During the war, which he spent in the helicopter squadron in Klatovy, the witness experienced the invasion of the Warsaw Pact troops. After his military service, he worked most of the years in the Sokolov brown coal mines, working his way up to a leading position even as a non-party member. After 1989, he became a guide, guiding mostly German tourists, among whom were also expelled compatriots. In 2023, he lived in Karlovy Vary. The memories of the witness were filmed and processed thanks to the financial support of the town of Cheb.