Otca s krvácajúcou rukou zbadal Nemec, poskytol mu prvú pomoc.

Download image

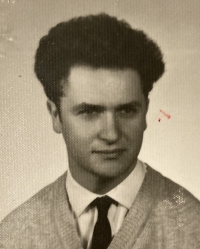

Ludovít Fischer was born on 7 January 1940 into a Jewish family of a physicist who studied in Prague and Zurich. After the establishment of the People’s Republic of Slovakia, he could only work as a teacher. The family was saved from deportation by exceptions. Before the outbreak of the Slovak National Uprising, his father taught at the trade academy in Banská Bystrica. After its suppression, from October 1944, they hid with a peasant in Kalište, who was the father of one of the academy’s students. Here they narrowly escaped detection several times and managed to survive until the liberation, although their father was seriously wounded during the fighting. Ludovit witnessed the burning of the village. Soon after the liberation, he moved with his parents to Bratislava, where he graduated from eleventh grade in 1957. He decided to follow in his father’s footsteps - he studied physics at the Faculty of Natural Sciences of Comenius University in Bratislava. During his compulsory military service he joined the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia in 1963. He returned to the faculty, where he worked as an assistant during his studies. After the invasion of the armies of the friendly armies on 21 August 1968, party checks were carried out from the beginning of 1970, during which he was “struck off” as an inactive party member. He could have remained at the faculty, but his progress was halted. He waited eleven years for recognition as an associate professor. In November 1989, he took an active part in the revolution and was a member of the strike committee. He became head of the department and a few months later was elected vice-dean for science and research. From 1997 to 2003 he was Dean of the Faculty of Mathematics, Physics and Computer Science. He and his wife have three children and seven grandchildren.