To become a dissident was not a matter of some conscious choice; instead, we somehow gradually grew into it

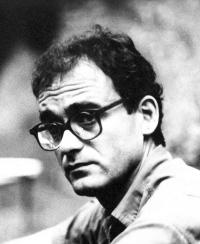

Karel Freund was born in 1949 in Košťany near Teplice. He was born in his father’s second marriage. Karel’s father was a doctor and as a Jew he spent several years in a concentration camp during the war, where he also lost his first family. When he finished elementary school in 1964, Karel began studying grammar school and after graduation he went to Prague, where he began studying Czech language and literature at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University in 1968. In 1970 he wished to transfer to the Faculty of Pedagogy to focus on special education, but instead he received his draft notice for two years of army service. After his return from the army he and his friends became involved in the unofficial cultural life centred on the informal circle called Šafrán. In 1977 he signed Charter 77 and two years later he joined VONS (Committee for the Defence of Unjustly Persecuted). After 1989 he began working at the Ministry of Interior. He worked there for several years and then he began working in the non-profit organization Sananim, which helps drug addicted people, and in the Children’s home Korkyně. Later he went to work in the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes. Karel Freund is now retired and he lives in Prague.