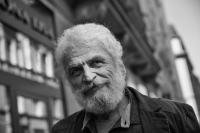

We have to keep dialogue open across the fences

Download image

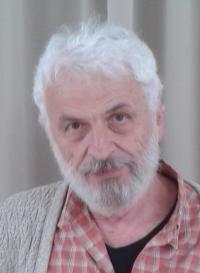

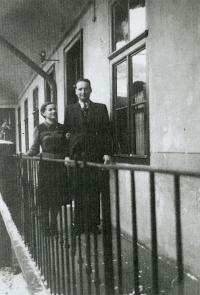

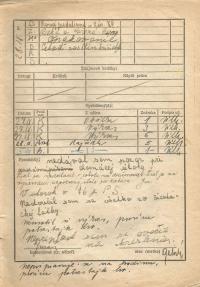

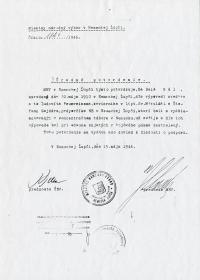

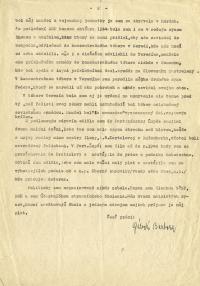

Fedor Gál was born on 20 March 1945 in the Terezín ghetto where his mother Barbora and his brother Egon were kept captive. He had never gotten to know his father Vojtěch Gál. The family was of Jeiwsh origin and used to own a large farm in the village of Partizánska L’upča in the Slovak region of Liptov. His father fought in the Slovak National Uprising. Following its suppression, the Gál family was caught and imprisoned in the Sereď concentration camp. Fedor’s father was transported to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp and died on the eve of the war’s end during a death march. His mother and two small sons survived and returned to L’upča where she tried to farm once again. However, the property was nationalized by the communists in 1948, and so she left with her sons for Bratislava where she worked at a scrapyard until retirement. Fedor Gál finished an elementary school in Bratislava and then a school of chemical engineering in Zlín. He was a worker in a chemical plant, and at the same time graduated from the University of Chemistry and Technology. He then worked in sociology and prognostics in several research institutes. In November 1989, he took active part in the Velvet Revolution in Bratislava and co-founded the political platform Verejnosť proti násiliu. For a short time, he was active in Slovak politics. After the breakup of Czechoslovakia in 1992, he moved to Prague where he lectured sociology at the Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University. He was among the founders of private TV channel Nova. He also established the publishing house G plus G, which focuses on books dealing with minorities, otherness and the Holocaust. Ever since 2009, he works as a film documentarist. He produced four feature movies and twelve short documentary essays. In the documentary Short Long Journey, he maps the life story of his father.