Thanks to our faith, we always managed everything

Download image

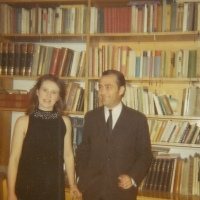

Alena Groulíková, née Stöckerová, was born on 14 May 1937 in Nové Město nad Metují as the only daughter in the family of Viktor Stöcker, the district commissioner of the political administration. Her father helped the partisans, yet after the war he was arrested and imprisoned for six months on suspicion of aiding the Germans during the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. After he was cleared by a people’s court, he returned to his post. In 1949 the family moved to České Budějovice. In 1956 she finished her studies at the grammar school and in 1957 she married Karel Groulík, they had seven children together, the whole family was strongly religious. Together with her husband, they were considered Christian dissidents in the České Budějovice diocese. During the normalisation period, her husband translated various banned books and publications and Alena Groulíková copied them in samizdat and distributed them among her friends. After the Velvet Revolution they were actively involved in the leadership of the Czech section of the Pan-European Union. In the 1990s, the Groulíks founded the Sudeten German Information Centre in České Budějovice and thus helped to promote Czech-German reconciliation in southern Bohemia. During her productive life she changed several professions, the longest period of time, from 1970 to 1990, was spent in the field of railway construction. In 2023, she was living in České Budějovice.