He wired the republic but hated communists

Download image

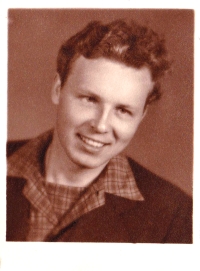

Jaroslav Hadraba has spent his whole life in Tábor where he was born on 13 April 1935. Even though he was only four years old, he remembers the arrival of Germans in town. The fact that his father František Hadraba was sent to forced labours in 1941 had a significant impact on his family. He sent a part of his income home; however, the family could only make a poor living from it. His father did not return until March 1945 when he managed to escape the forced labours on the second try. Nevertheless, he had to hide until the end of the war. Jaroslav Hadraba´s worst experience of that time is the air raids on Tábor train station at the end of April 1945. During the bombing of an armoured train, the bombs fell also on houses in the Blanické suburb where the witness lived at that time. In 1948, Jaroslav started his apprenticeship as a carpenter in Lišov, seventy kilometres away. When he returned after his first holidays, he found out that the workshop had been in the meantime nationalised by the communists. That is why he finished his studies at a vocational school. In 1954, he enlisted in the army engineers. As he admits, he helped “wire” the republic [= build the iron curtain – trans.] at that time. His opinions and those of his father František, a convinced communist, diverged gradually to the point when he (his father) ordered him to return his keys so that he could not visit his mother Růžena Hadrabová. He got married in 1957. He and his wife Marta (née Setková) shared similar attitudes toward the communist regime. Her father, Tomáše Setka was facing prison because of the song ‘Máme Prahu stověžatou a v ní Martu prdelatou‘ (We have Prague with a hundred towers and Marta with a fat bottom in it) which was an allusion to the physical proportions of President Gottwald’s wife. In August 1968 Jaroslav managed to remind his father of the fact the soldiers who were occupying us were not the same soldiers who liberated Czechoslovakia in 1945. His whole life, he has remained loyal to Tábor, the same carpentry company, and also to his wife with whom he celebrated their 65th wedding anniversary on 15 June 2022 in the Tábor home for the elderly.