He emigrated after the occupation. Painful sadness brought him home

Download image

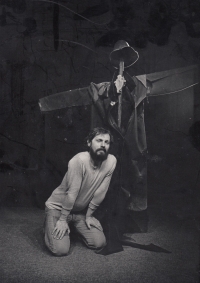

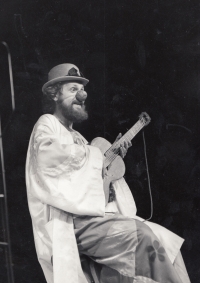

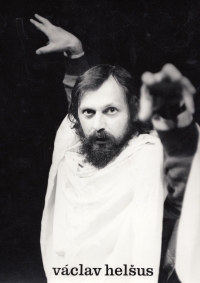

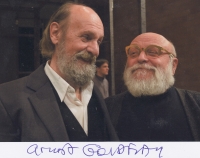

Václav Helšus was born on March 6, 1947 in Louny, where he lived with his parents and two brothers in the building of the local mill. In the mid-sixties, he began to study at DAMU under the guidance of professor Vlasta Fabianová and director of the Realist Theater Karel Palouš. The occupation of Czechoslovakia in August 1968 and the subsequent reaction of the public disappointed him so much that he decided to emigrate to Great Britain at the end of the year. For almost a year, he supported himself by manual labor and visited theaters in his spare time. However, after a one-year stay in the West, he returned to Czechoslovakia and graduated from DAMU in the academic year 1969/1970. After successfully graduating, he joined the Kladivadlo in Ústí nad Labem for a few months, and later the Ypsilon Theatre, which was operating in Liberec at the time. He excelled in several famous productions, but it was also there that he met his future wife, Dagmar Gregorová. In 1978, the Ypsilon Theater decided to change its location and the troupe moved to Spálená Street in Prague. However, Václav did not like the new poetics of the theater very much, so he took the opportunity and went to work at the F. X. Šalda Theater in Liberec, where (with a two-year break spent at the National Theater) he remained until the revolution in 1989. In the revolutionary days of November, Václav and the Liberec theater troupe joined the strike. He and his wife, Dagmar Helšusová, drove around North Bohemian factories, talking to workers or delivering speeches to crowds of protesters. Later, both were at the birth of the Liberec Civic Forum. Václav Helšus continues to be an actor to this day. In 1995, he was nominated for the Thália Award for the role of Vávra in the theater play Maryša. In 1999, he won the prize for the best acting performance at the Festival of Czech Theater in the play Crime and Punishment. He has also acted in a number of film and series roles. In 2020, viewers could see him in the movie Modelář.