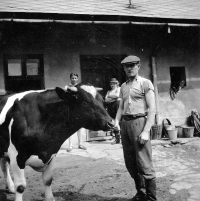

If it was not for the communists and collectivisation, I would have been a farmer all my life

Download image

Josef Hlubek was born on 17 September 1939 in Hlučín, in the former German Reich. His parents farmed a farm with sixteen hectares of fields, one of the largest in Hlučín. He remembers many dramatic events from the World War II in Hlučín. Their farm was heavily damaged by a phosphorus bomb in April 1945. After the war, the family escaped deportation to Germany at the last moment. After 1948, the parents resisted pressure for several years to join a unified agricultural cooperative. The father was publicly denounced by the communists as a kulak. Joseph was expelled from agricultural school because of his background. After compulsory military service, he started working as a truck driver. For almost twenty years he worked as a foreman of freight transport in ČSAD Hlučín. After the Velvet Revolution, he got back twelve hectares of fields and meadows which used to belong to his parents in restitution. He then farmed privately for more than twenty-five years. He was instrumental in the repair of many crosses and small religious monuments in Hlučín. In 2022 he lived there.