I’m a Sudeten. Not geopolitically, but geographically.

Download image

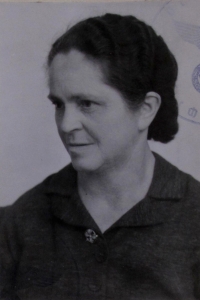

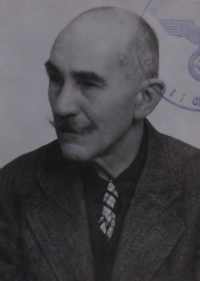

Osvald Hons was born on 2 April 1938 in Mimoň into a mixed Czech-German family. The Hons family lived through World War II in Mimoň, where at the end of the war they witnessed the bombing of the town. After the seizure of the borderlands, his father refused to accept the new citizenship of the Great German Reich and was sent to work in Germany. Because the family was strongly left-leaning, its members did not have to be included in the post-war expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia. Osvald Hons’ family was therefore able to remain in Mimoň after the war. In 1945, he entered the second grade of a Czech school, where he quickly acquired Czech. After graduating, he entered a glassmaking school in Nový Bor, where he gained knowledge in glassmaking technology. After completing his compulsory military service from 1957 to 1959 in Slovakia and in Červená Voda, he returned to school. He completed his education at the Higher Industrial School of Glass in Nový Bor and started working at the Research Institute of Applied Glass. After the occupation of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact troops, he was expelled from the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia after party checks and declared a right-wing opportunist. Later he worked in the labouring professions until 1971 when he joined the uranium mines in Hamr na Jezeře as a miner. After a serious accident in 1983, he worked only on the surface and then retired. Osvald Hons lived in Mimoň even at the time of filming (2024) and devoted himself to his greatest hobby, which is regional history. We were able to record his story thanks to financial support from the town of Mimoň.