White, black or yellow. Love one another, you are here just once

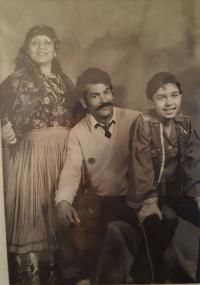

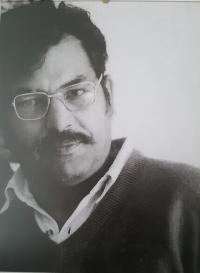

Agnesa Horváthová, née Marcinová, was born on April 4, 1949, in the village of Ondavské Matiašovce, Eastern Slovakia, as the oldest of six children into a Romany family. Her father made his living mainly as a cow shepherd or travelled to the Czech territory for work. Her mother stayed at home, taking care for the children. When obtaining their livelihood and taking care for the children, both parents were helped by the grandmother from the father’s side. At home they spoke the East-Slovakian dialect of Slovak. She liked the school, wanted to get professional training but her mother did not allow it because of the family’s poor financial situation. In the early 1960s the family moved to Jinočany near Prague. At seventeen she met her future husband Milan Horvát, in whose family she learned the Romany language. In the 1970s they had four children. Mrs Horvátová worked on a number of positions, mainly as a labourer. In the 1980s she founded, together with her family’s members, the Romany folklore ensemble Perumos, with whom she performed all over Europe. It was then that she met the Gypsy scholar who inspired her to her own work. This gave rise first to individual stories and poems, then to a whole book in 2003. In 1989 she, her husband and the ensemble members engaged in politics as members of the Romany Civic Initiative. These activities led to the growing sense of dissatisfaction with the conditions of Romany people in the Czech Republic and in the life in fear, augmented by threats and racially-motivated assault on her son. This dissatisfaction culminated in 1996 by the family leaving for Belgium. The closest family of Mrs Horvátová returned three years later, while the second part of the family and the Perumos ensemble remained in Belgium. Mrs Horvátová is now retired, enjoys the achievements of her children who inherited her artistic gifts and believes that they will continue in the legacy of the ensemble.