My dad got the death penalty when he was twenty-three, and he knew it wasn’t some movie or theater, because the heads were really rolling around

Download image

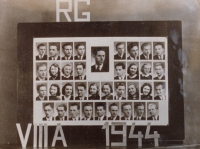

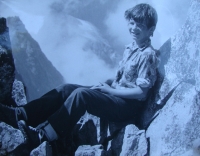

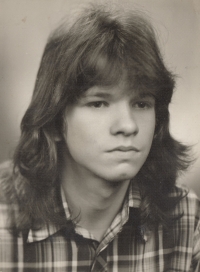

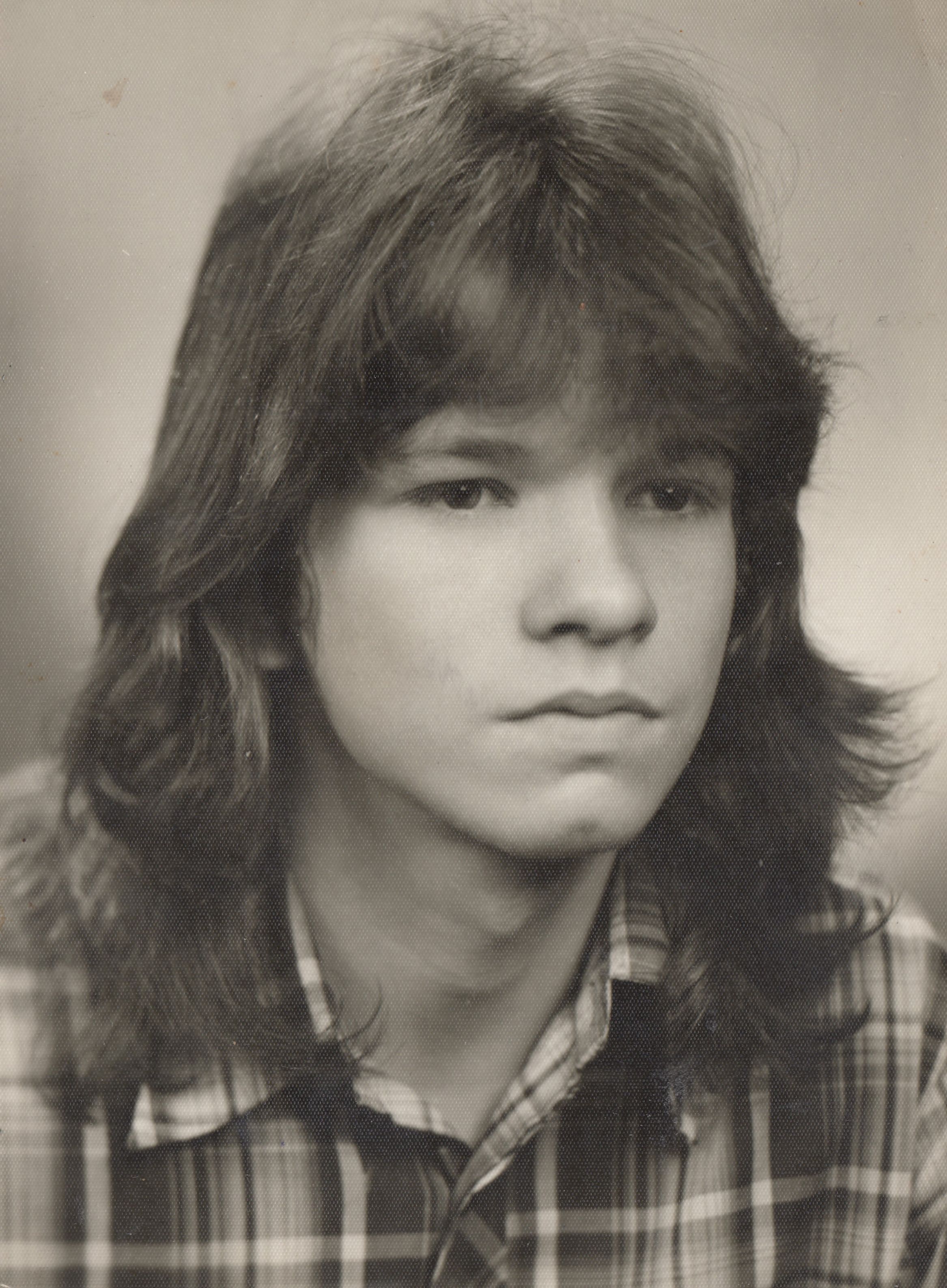

Zdeněk Hovorka was born on 29 March 1963 in Pilsen to Maria Hovorka, maiden name Belzová, and Miroslav Hovorka. His mother’s brother Robert Belza won many awards as a successful weightlifter. His great-grandfather Johann Hovorka earned the first lowest noble title for his service in the army. His mother was totally deployed in production in Kiefersfelden during the war, his father as a diver in Bordeaux, the base of the Italian and German submarine fleet. After that, he apparently carried the dead out of houses destroyed by air raids in Munich. On October 1, 1947, father enlisted in the army in Tábor, where, together with the clergyman Robert Bednařík, he formed a group of anti-communist-minded men, which was infiltrated by Klemen Hlásenský, a provocateur agent deployed by State Security and connected with the case of P. Josef Pojar. Miroslav Hovorka was arrested and sentenced to nineteen years of hard labour in a mock trial for military treason. From April 13, 1948 he was imprisoned in Domecek in Hradčany, then in Pankrác, in Plzeň in Bory and in the Correctional Labour Camp in Opava, where he worked on the mine shaft. He was released on amnesty on 12 April 1956 after eight years in prison. Zdeněk Hovorka trained as an electrician in Plzeň and began working for Water Works. In 1983 he graduated from the Škoda Secondary Vocational School in Skvrňany, but he did not complete his studies at the University of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering in Pilsen. In order to avoid the war, he joined the Dobré Štěstí mine near Dobřany, where he finished as a gunner in 1991. In 1985 he had to enlist in the army in Pilsen, Slovany. In 1989 he signed the petition Several Sentences. On 3 February 1990 he took part in the march to Bavarian Iron Ore. From 1991 to 1994 he worked in the company Elektrizace železnicce Praha, which sent him to Germany and France for assembly. On 13 February 1996, he married Iveta Krausová from Plzeň in Florida, and they later raised two children together. Zdeněk Hovorka has been teaching at the Secondary Vocational Electrical Engineering School in Pilsen since 2020. At the time of filming (2022) he lived with his family in Vejprnice.