The tennis troublemaker didn’t listen to the communists. He didn’t give up his cross or his mane

Download image

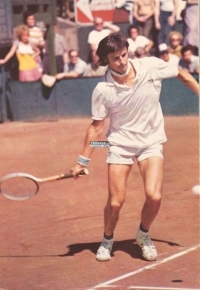

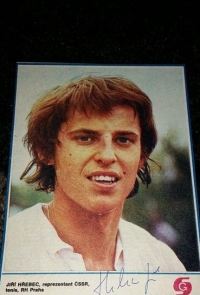

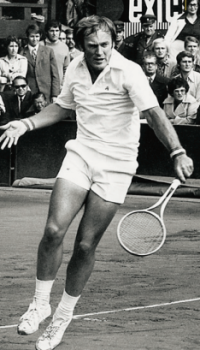

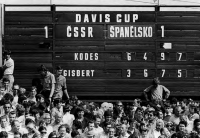

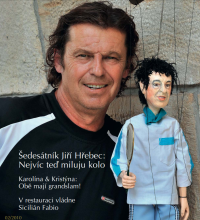

Jiří Hřebec was born on 19 September 1950 in Teplice, where he grew up with his three years older sister Marcela and his parents Josef and Vera. They both played tennis there. Their father supported them unconditionally in sports. Jiří Hřebec won his first tournament at the age of nine. In his childhood and youth he won the national championship in the younger and older pupils and also in the youth. Because of tennis, he moved to Prague, where he lived with his grandmother and later at the Red Star hostel, of which he became a member. At the age of fifteen, he entered the Secondary Surveying School in Prague, but because of the top sport, he had no time for it and was expelled after two years. He began to play tennis professionally, fighting for the Red Star in the first national league. From the age of fifteen, he went to international tournaments and became known for his attacking and colourful tennis. His reputation was marred by bad behaviour and violent tantrums. He entertained the crowd with his witty catchphrases. In 1972, he made his Davis Cup debut, beating Spain’s Antonio Muñoz 3-0. He was the youngest of the famous national team of Jan Kodeš, Vladimír Zedník, Jan Kukal and František Pála. In the Davis Cup, he won against the legendary Australians John Newcombe and Tony Roche, among others. In 1975, thanks to his merit, Czechoslovakia reached the final of the Davis Cup. There he won against Ove Bengtson and lost to Björn Borg. The national team lost to Sweden 2:3. In singles, he won three World Series tournaments, and in 1975, in the final in Basel, he defeated the Romanian Ilio Nastas, who triumphed a few months later at the Masters tournament, designed for the best players on the planet. In 1978, he quit the Davis Cup due to his participation in a small tournament in Austria, where he entered without official permission from tennis federation officials. He had only the verbal approval of the Davis Cup team captain Antonin Bolardt. However, he later denied that he allowed Jiri Hrebec to play in Austria. The tennis player lost his passport for four months and could not travel to important tournaments. He dropped down the ATP rankings and ended up with the national team in the Davis Cup. He toured smaller tournaments and received permission from the communist authorities to work as a coach in Augsburg, West Germany. When it expired after three years, he asked for an extension. However, he did not get approval, so he stayed in West Germany with his family and became an emigrant. He returned to his homeland in 1997, while the rest of his family remained in West Germany. He worked as a coach at the tennis federation during the era of chairman Jan Kodes and later as a coach for his charges at the ČLTK Prague. He trained the great Czech tennis players Jan Hernych, Iveta Benešová and especially Markéta Vondroušová, the winner of Wimbledon 2023. In 2024 Jiří Hřebec lived in Prague and was married for the second time. He had two daughters from his first marriage and one from his second.