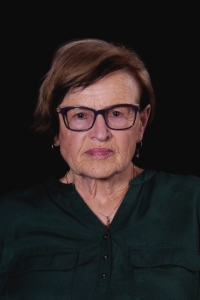

Justice yes, but hate no

Download image

Marie Hrudníková, née Tobiášová, was born on 21 September 1943 in Senice na Hané to parents Josef and Marie Tobiášová as the eldest of three children. Her mother Marie, née Tylová, came from Cakov, her father from Senice. Both families had farms. Uncle Josef Heřman Tyl, a Premonstratensian monk, was persecuted by the Nazis and the Communists. During the war, he underwent concentration camps. In the 1950s, he was sentenced in the political trial of Pícha and Co. for treason to 12 years. He also served his sentence in the Jáchymov camps. In 1946, he became prior of the monastery in Teplá and in 1989, its abbot. In the 1950s, the family was impacted by collectivisation. They had to meet the high supplies, their property was taken away. In 1957, they joined a unified agricultural cooperative (JZD). Marie and her siblings had problems with their studies because of their cadre profile. In 1960, she finished the eleven-year school in Litovel, and between 1960 and 1962, she studied an economic follow-up study in Mohelnice. She then worked as an accountant all her life. In 1966, she married Vojtěch Hrudník, an electrician who came from an agricultural family from Přestavlky. After their marriage they lived in Senice na Hané, from 1973 in Olomouc. They raised three daughters together. In 2020, at the time of filming, they lived in Velký Týnec.