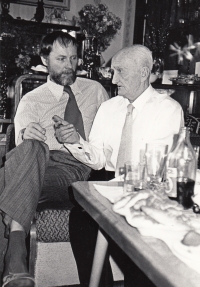

Journey to African studies led through a factory

Download image

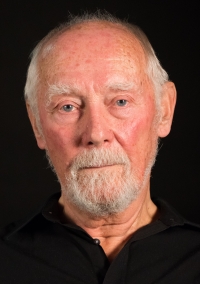

He was born on the 23rd of March 1935 in České Budějovice. His father was a lawyer and an opera singer at the same time, his mother was a daughter of a clerk. The “bourgeois” family living in a First Republic family house in the suburbs of České Budějovice called “Pražské předměstí” found themselves on the wrong side of imaginary barricade of class conflict in February 1948. Therefore, Otakar has been dealing with problems connected with his non-working-class origin for his whole life: the opportunity to study was repeatedly denied to him and he could pass the secondary school leaving exam only after two years of working in a factory. He was admitted to Faculty of Arts during temporary release in 1956 but he was expelled after four years of history studies because of “cadre reasons”. His teachers’ solidarity helped him because they let him pass the State leaving exam on their own. In 1962, he started to work in The Oriental Institute of the Czech Academy of Science, learned two African languages, did his doctorate and became Africanist. He had to leave the Institute in 1973. He was a teacher at elementary school for sixteen years before he could return to The Oriental Institute after the revolution in 1989.