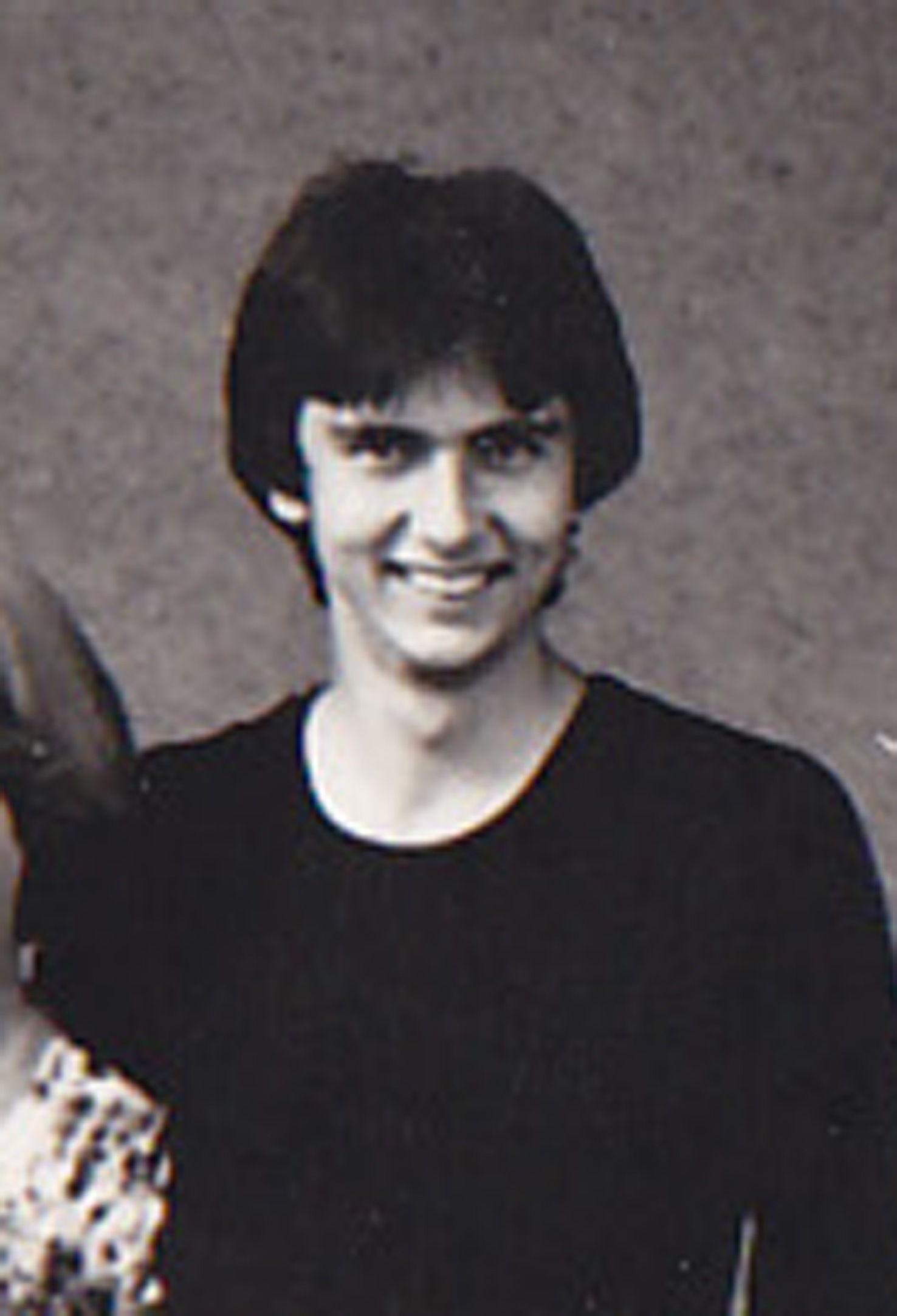

I was supposed to be guarding the border against trespassers

Download image

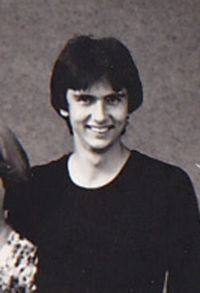

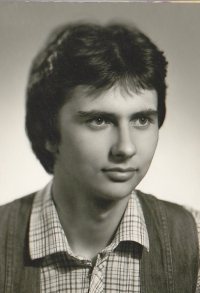

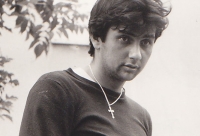

Zdeněk Hůrka was born on 15 April 1960 in Pilsen. Both of his parents taught at the Klement Gottwald Secondary School of Economics (now the Business Academy), but his father Lubomír Hůrka was professionally demoted during the normalisation period for signing the Two Thousand Words declaration. Zdeněk Hůrka came out of the primary school with expanded language teaching with the cadre assessment sstating: “The family environment does not guarantee an education towards socialism.” In spite of his excellent school results, he therefore entered the apprenticeship of mechanical locksmith completed with secondary school graduation at the Škoda factory in Plzeň. In 1980, he managed to get an approval for buying foreign currency and hitchhiked through capitalist foreign countries with a friend. In 1982, he entered compulsory military service with the Border Guard in Domažlice. Thanks to his brilliant knowledge of German, he was to work as a so-called searcher, i.e. to walk around in civilian clothes and pick out possible border trespassers. He also interpreted interrogations of people who were detained in connection with crossing the state border. After the Velvet Revolution, he was finally able to pursue his professional career more freely and pursue his hobbies, working, among other things, as a presenter of the first West Bohemian private radio FM Plus.