It´s like this with time - it just keeps running forward; and it never goes backwards.”

Download image

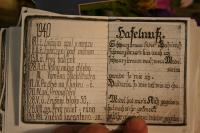

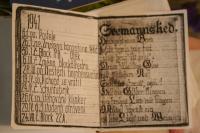

Mr. Karel Hýbek, Ing, was born on October 2nd 1919 in Kostelec, beyond Labem town. His father was a former Austro-Hungarian soldier. He also served in the Czechoslovak army and finally also in the protectorate government troops. The family lived in Jindřichův Hradec town and in České Budějovice. After that they settled down in Rokycany where Karel Hýbek attended high school. Czech Universities were shut down in November of 1939, ending Mr. Hýbek’s studies at the Mechanical Engineering College of Prague. After the incidents which occurred during the funeral of Jan Opletal, Karel Hýbekwas one of the chain of students that were arrested in the Hlávka dorm. He was deported with other students to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. He had been released in 1942, just before the R. Heydrich assassination. He returned back to his parents, who moved in the meantime to Benešov town. After the liberation he underwent a short military training at the army academy and completed his academic studies which had been interrupted by the war. In June of 1949 he begun to work as an assistant at the Mechanical Faculty and he remained there until 1952. After that he worked at the Research institute of the ferrous metallurgy. He stayed at this position until 1973. After that he moved to the Research Institute of Engineering where he remained until 1989.