The family repaired 37 churches in the Most area. Some of them were immediately demolished by the Communists

Download image

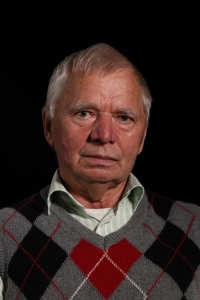

Ladislav Hylena was born in Křivsoudov on 14 November 1945, but the family moved to the Bohemian Forest in 1947. In 1949 his father copied out a pastoral letter, and his sons distributed it in churches in the area. As a publican, his father overheard some guests in the pub planning an illegal border crossing in 1950. The group was caught by the authorities, and everyone connected to the case was imprisoned, including Hylena Sr. He spent a year and a half in prison camps in Jáchymov and near Příbram. After his release, the Hylenas had to move out of the Bohemian Forest, first to Týn nad Vltavou and then to Hora Svaté Kateřiny in the border region of the Ore Mountains. In the 1960s and 70s, the whole family dedicated their free time to repairing dilapidated church buildings there. They repaired a total of 37 churches. Many of them were subsequently demolished to make room for expanding surface mines. Ladislav Hylena trained as a bricklayer and worked on construction sites first in Most and then in Prague, where he helped building housing estates in Spořilov, Prosek, and Skalka. After 1989 he was employed as a caretaker at the Catholic seminary in Dejvice. He is married and has three children.