If I ran like I was running for my life, a Russian soldier wouldn’t have shot me

Download image

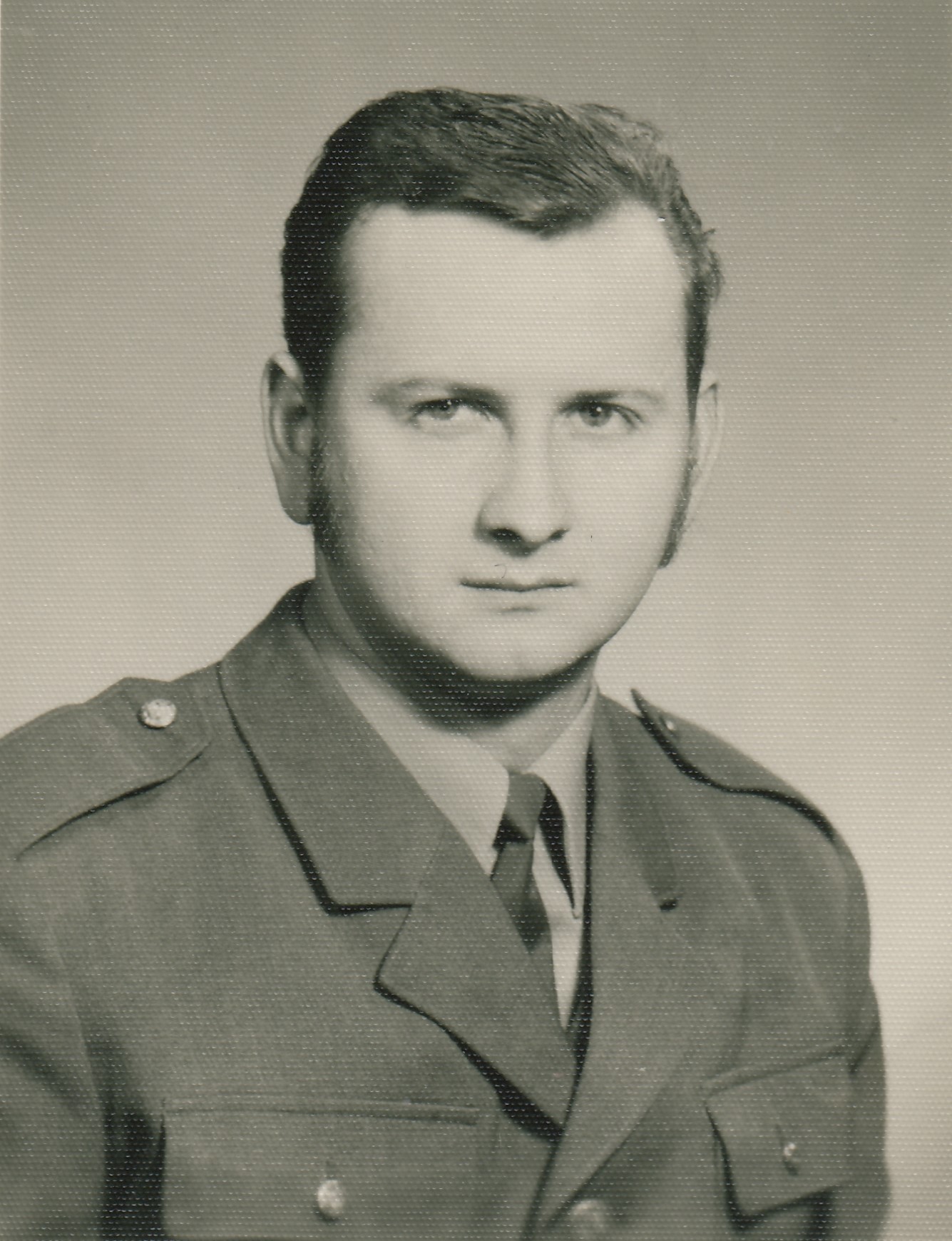

Jiří Hýř was born on 9 December 1948 in Habartov near Sokolov. As a child he lived with his parents in the old Most before its demolition, later they moved to Lubenec. He went to study at the University of Agriculture in Prague. After the first year, when he stayed with his parents in Lubenec during the summer, Czechoslovakia was occupied by the armies of the Warsaw Pact. In Lubenec he participated in hiding road signs to protest the occupation. After returning to school in Prague, he went with a group of students to discuss with Soviet soldiers who had their headquarters on náměstí Hrdinů. While two of the students were discussing with the soldier, Jiří Hýř and another student thought that they could take away the Soviet red flag that they had raised in front of their headquarters. The Soviet guard noticed this and started shooting at them with a machine gun. Jiří Hýř’s leg was shot through as he fled, and he also wounded a random passer-by. Jiří Hýř almost lost his leg, but doctors saved it in the end. After this incident, he lost the desire to continue his studies in Prague and left the school. He went back to Lubenec and eventually moved to Valeč in 1971, where he started working at the local forestry administration and stayed until the revolution. He often dealt with the leadership of the local Soviet garrison about incidents caused by their soldiers. In 1990 he finally became the first post-revolutionary mayor of the village. Later he worked at the Valeč castle as a maintenance man. In 2024 he was still living in Valeč as a pensioner.