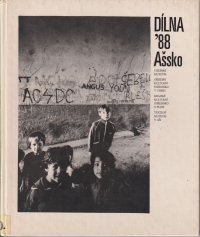

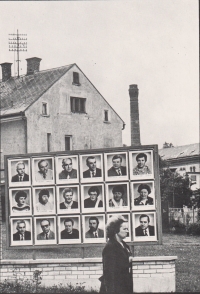

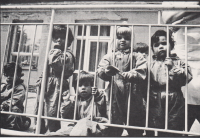

It bothered them that we were showing the contemporary world as it really was

Download image

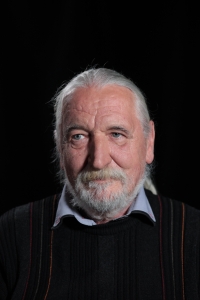

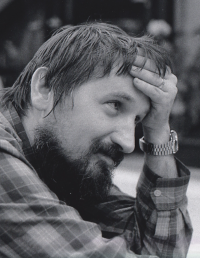

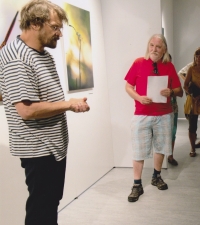

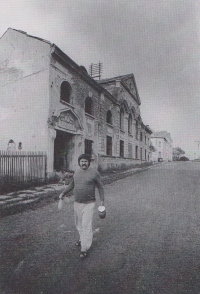

Zbyněk Illek was born in Mariánské Lázně on 20 March 1954. His father Adolf worked as a master blaster at the Jáchymov uranium mines, his mother Eliška was an invoicing clerk at the West Bohemian Timber Operations. He attended a boy scout club led by Jan Harvánek in his childhood. He enrolled in the grammar school in Mariánské Lázně in 1969, witnessing the onset of the normalisation. After graduating in 1973, he studied at the Faculty of Education in Plzeň, majoring in first stage teaching and art education. He founded a photography club during his studies. He graduated in 1977, got married, had a son and moved to Cheb where he started teaching at a primary school. Completing his military service in Uherské Hradiště, he returned to the school where he worked until 1982. To avoid pressure to join the Communist Party, he went to work at the District Cultural Centre as a photography, film and art methodologist. Founded Gallery 4 in Cheb, focusing on photography, in 1985. Between 1986 and 1989, he completed a distance course at the Institute of Fine Art Photography in Opava. His Gallery 4 organised exhibitions of domestic and foreign photographers, often displeasing the regime. He was interrogated by the State Security several times. In 1990, Zbyněk Illek was elected as an independent candidate to the Cheb Town Hall in the first local election. He continued the activities of Gallery 4, continued to promote photography as a distinctive artistic genre and initiated, among other things, the multicultural project Cheb Courtyards.