A man behaves in a certain way, but that doesn’t mean he’s in the resistance. It’s a matter of attitude to the situation

Download image

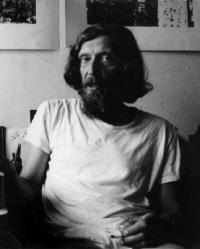

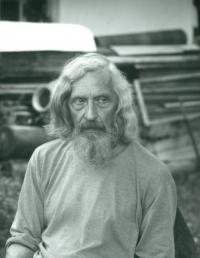

Painter and graphic artist Jiří Voves was born on 4 January 1945 in Pardubice. He only vaguely remembers the period following the Communist coup in 1948, his parents tried to shelter him from the vagaries of the time. But even so he remembers the businessmen put on display in the windows of their own shops, or the police visits in their house and the confiscation of the property that came from his grandfather’s shop. In the 1960s he began studying architecture in Prague. His university years and the relaxed political atmosphere of the time had a euphoric effect on him. He travelled through France, visited theatres, concerts, exhibitions, and cultural events. In the 1970s after completing his studies he did his military service in the seclusion of the Jince barracks, he was then employed at an architectural office. When he refused to sign the so-called “Anti-Charter” in 1977, he was fired. He went freelance and earned his living with painting and graphic design for books. Shortly after November 1989 he oversaw the moving of artist Zdeněk Kirchner’s collections from France to the Czech Republic. For this purpose he established the civic society Paměť (Memory), which became an important cultural centre: organising exhibitions, reading sessions, discussions, theatre plays, concerts, etc. After his wife’s death the witness was not able to continue running the studio, and so he handed the premises in Soukenická Street over to Andrej Krob and Divadlo na tahu (Theatre on the Move). Jiří Voves now lives in the settlement of Zadní Kopanina, where he devotes himself to painting and graphic design.