Of the people who studied in Russia, only a nark could stay a Communist

Download image

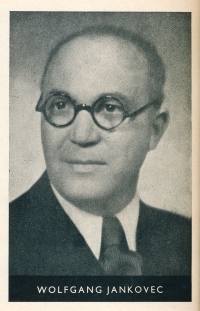

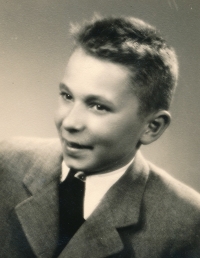

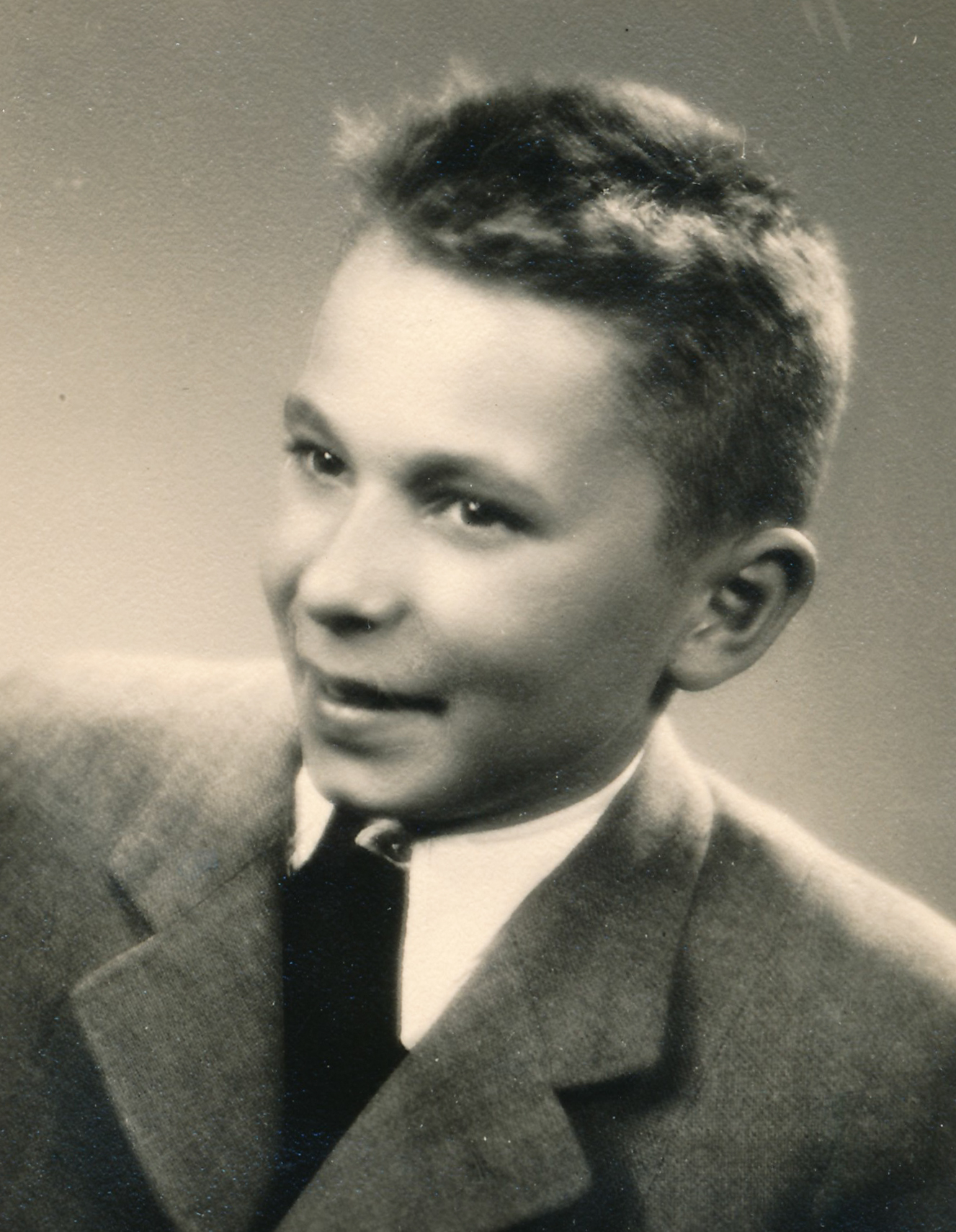

Petr Jankovec was born in Prague on 22 June 1935 in the family of Wolfgang Jankovec and Ludmila Jankovcová. Both parents were active in the anti-Nazi resistance movement but while his mum was not imprisoned, his father was arrested on 10 December 1941 and executed in 1944. A street in Prague 7 Holešovice is named after him. Petr spent the war in Prague and partly also at his aunt´s where he lived to see the liberation in May 1945. He remembers their family friend Josef Fischer whom they helped to hide from the Nazis, the arrest of his father and the visits to the headquarters of Gestapo at the Petschek Palace, his mom´s bravery, and also the forced labours which she was assigned to in 1944. After the war, Ludmila Jankovcová entered high politics for the Social Democrats, she held party positions and served as Minister of Industry and Food after 1948. She was a vice-chairwoman of the first and second governments of Viliam Široký, she resigned in 1963. After the invasion of Warsaw Pact troops, she was expelled from the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia during the political screenings, and she signed Charter 77 in 1977. Petr graduated from a grammar school in 1953 and was admitted to the Faculty of Engineering. After two semesters of studies, he applied to study in the Soviet Union where he wanted to study turbines. However, he was sent to Kharkiv to a field which he did not want (to study) and he got to Moscow Power Engineering Institute after a year and a half of studies. He graduated from the school in 1960. He got married and started a family in 1961. They settled down in Pilsen where he got a job in his field. His stay in the Soviet Union changed his opinions on politics. After the invasion of Warsaw Pact troops, he was a leading Pilsen activist, he promoted passive resistance toward Soviet soldiers, negotiated with the Soviet leadership, etc. He was fired from work because of political reasons in 1971 and he worked as a blue-collar worker. He got back to working in his field in 1982. The revolutionary year of 1989 found him as a test engineer on the construction sites of nuclear power plants, most of the time at Mochovce, but also at Dukovany and Temelín. After 1989 he won a selection procedure for the post of Director of Nuclear Management at the Škoda company, where he worked for two years before Škoda was privatised. He then worked out of his field in the private sector as a self-employed person until his retirement in 1997.