It was no bed of roses anywhere at the coking plant. Even the retired miners were shaking their heads.

Download image

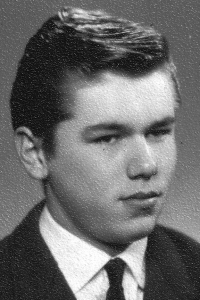

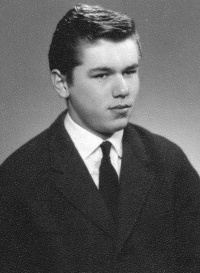

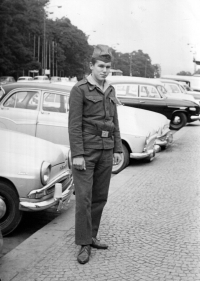

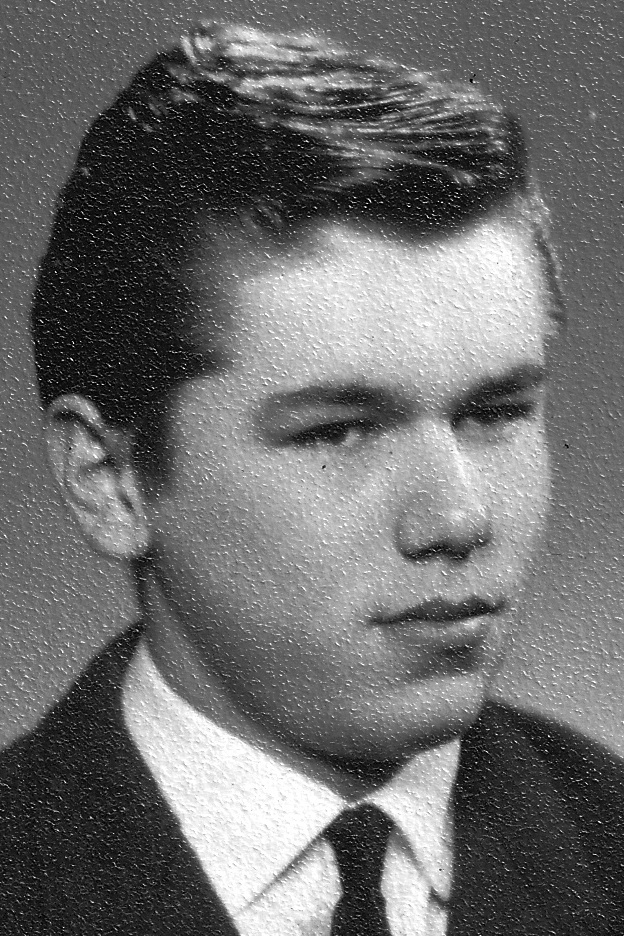

Ladislav Jaworek was born on July 16, 1946 in Dolní Marklovice, a part of Petrovice near Karviná. He grew up in a Catholic family in Karviná-Nové Město. His father worked for over thirty years as a coker at the coke battery in Karviná. He trained as a locksmith for the Coke Plant of the Czechoslovak Army. He graduated from an apprenticeship in Opava. He is a witness of coke production and coke plant operation under the communist regime. In August 1968 he protested against the entry of Warsaw Pact troops. His father was expelled from the Communist Party because of his opposition to the occupation. After the decline and closure of the coke plant in 1997, the witness moved to the maintenance of the Karviná Czechoslovak Army Mine, where he worked until his retirement. In 2022, he was living in Karviná.