My dad was hiding the mother from the Nazis in a darkened room for five years

Download image

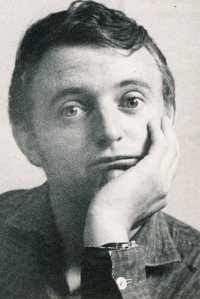

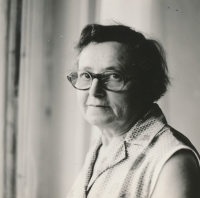

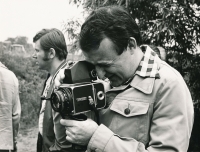

Jan Jelínek was born on 19 July 1940 in Prague to a mixed Czech-Jewish family of merchant Josef Jelínek and his Jewish wife Marie, née Ledererová. John had an older brother and a younger sister. The family lived in Liberec, where the father had a textile shop. At a time when his wife and children were threatened to be transported to Terezin, Josef decided to hide his family in his father’s house in Hořepník near Pacov, which he succeeded. Marie hadn’t been out of a small darkened bedroom for five years; little Jan, with his father’s blond hair, could walk out on the street. After the war, his father took the family back to Liberec, but in 1947 he died as a result of the war stress of disclosure. Widowed Marie with three children moved to Nymburk. Jan graduated from the local grammar school and then attempted to study at FAMU, but was not admitted due to cadre reasons. He enlisted in the army in České Budějovice, got married and after his return he settled down with his wife in Mladá Boleslav, where he found a job in an educational house. He was in charge of educating young photographers and amateur filmmakers. In the 1960s he went to study journalism, which he graduated in 1968, and then joined the Short Film. For more than twenty years he has been making reports for the Czechoslovak Film Weekly. In the mid-1990s, in cooperation with the Jewish Community, he made fifty interviews with Holocaust victims. They were published in a book called „And where was God ...? “.