In my dreams I was walking on the Charles Bridge

Download image

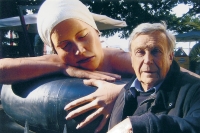

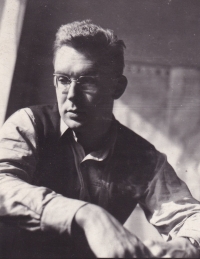

Oldřich Jelínek was born in Košice on February 26, 1930, in the family of a Czech industrial school professor. He was fascinated by the technique, which is a frequent object of his creations, since childhood. Even as a boy, he knew every car or motorcycle in his neighborhood. He soon began to paint his observations, in which his perceptive parents greatly supported him. In 1938, when the national tension in Slovakia escalated, the family decided to return to Czech. They found a new home with their relatives, in the family villa in Podolí, Prague. After completing the elementary school of St. Voršila he startedstudying at the secondary grammar school in Vratislavova Street. Adolf Born became his classmate there, in whom Oldřich Jelínek gained not only an accomplice for student mischiefs, but above all a long-time friend and collaborator. Both young men continued their studies first at UMPRUM (Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague), then at AVU (Academy of Fine Arts, Prague) under the guidance of Professor Pelc. Oldřich Jelínek spent his student years immersed in jazz, surrealism and the life of the literary underground in the circle of friends Egon Bondy and Ivo Vodseďálek, to whose samizdate edition Půlnoc he also contributed. After successfully graduating from the academy, he worked primarily as an illustrator of books for young people, cartoonist of Dikobraz, Mladý svět and many other leading magazines, which greatly contributed to his popularity. He experienced the events following the invasion of the Warsaw Pact troops in Switzerland, where he worked on the production of an animated film. Although in the years of normalization, thanks to his foreign successes, he was able to continue creating and exhibiting, he felt a deep disappointment in the state of society. He found encouragement in a circle of friends, among whom was also a group of artists from Trutnov region, thanks to whom he met Václav Havel. Oldřich Jelínek decided to leave the republic at the age of 51. This “jumping off the bridge”, as he calls his decision today, was driven by his desire for freedom and, above all, his wife’s wishes. The first years spent in Munich, which became his new home, were difficult. When the Czechoslovak Artcentrum “recommended” German galleries not to buy his works, Oldřich Jelínek literally had a new professional start. He made a name for himself in Germany by creating for advertising agencies and later as an artist and cartoonist for the weekly magazine Computer Woche. He lived a total of forty years in emigration, but “in his dreams he still walked across the Charles Bridge”. He returned to his beloved Prague permanently in 2021, where he lives and still creates (2022).