Cleaning up my father’s unmanageable job didn’t seem like enough, so we were charged with economic crimes

Download image

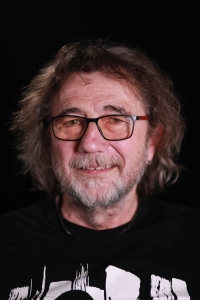

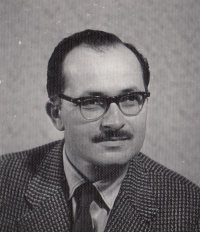

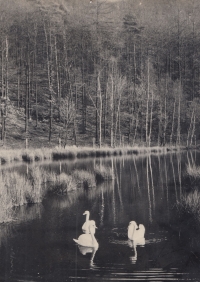

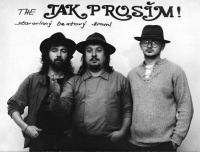

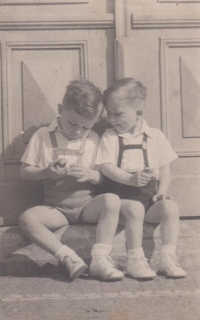

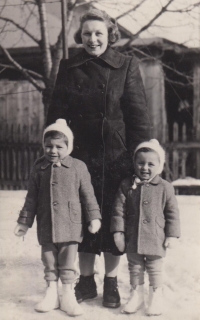

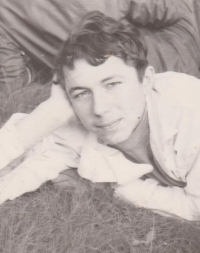

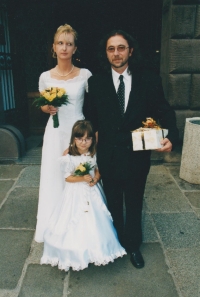

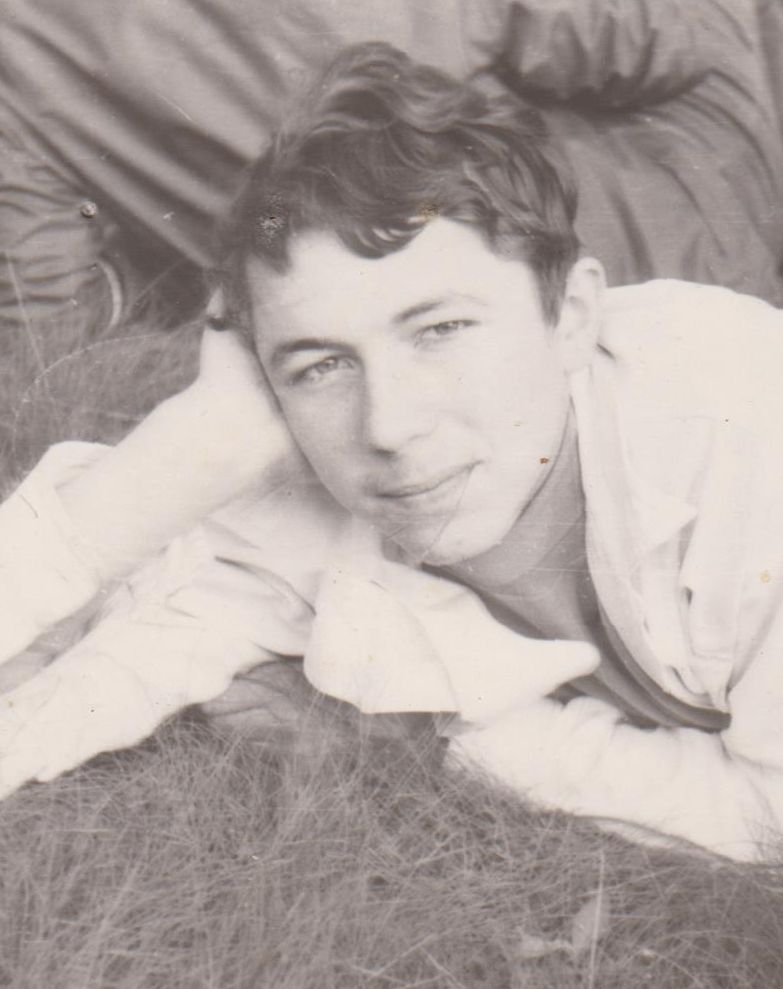

Jan Kaňák was born on 9th January 1953 in Rychnov nad Kněžnou. His parents, Karel Kaňák and Jarmila Kaňáková, maiden name Bastlová, came from Pilsen. At the time of their son’s birth they lived in Opočno because of his father’s job, but the hospital there was under reconstruction. The likeness of his great-grandfather Hynek Kaňák, a Plzeň bagpiper, was immortalised by the painter Augustin Němejc on the curtain of the J. K. Tyl Theatre. His parents were totally deployed during the war. His father, by nature of his adventurous nature, was a member of the Communist Party from 1949 to 1967, but he had already broken with its views. In 1956 he founded the Sofronka Arboretum in Pilsen-Bolevec, which he often had to fight to survive. In the 1960s, the arboretum became a meeting place for important artists, including Miroslav Horníček and Jan Werich. Jan Kaňák did not get into medicine after graduating from high school in 1972 because of his inadequate cadre profile. From 1974, after studying medical school, he worked as an X-ray laboratory technician in the pulmonary and tuberculosis hospital in Janov u Rokycany. In 1977 he had to resign for health reasons, but this also allowed him to avoid a staff meeting at which he was to be nominated as a candidate for the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. Like his father, he began to work in Sofronka. Around 1980, he was questioned by the Economic Crimes Police about the alleged fraudulent sale of pine seedlings. Practically, however, this was an interrogation by State Security to obtain information or to establish cooperation. The Sofronka Arboretum often balanced on the brink of closure. In 2010 it was transferred to the Public Farm Administration of the City of Pilsen. At the time of the filming in 2013, the witness was working as a freelancer in Sofronka and continued to preserve his father’s legacy. He is married for the second time and has two daughters and a son.