The journey to the Great Book of Liberec began with the sabotage of political training

Download image

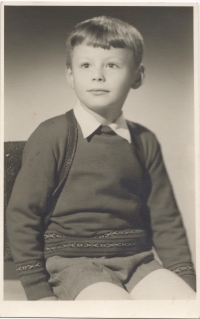

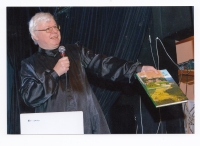

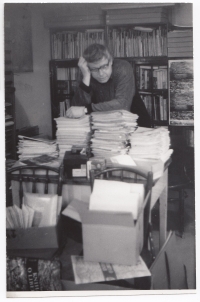

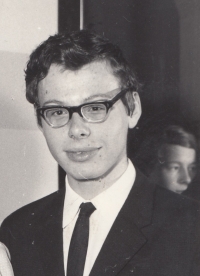

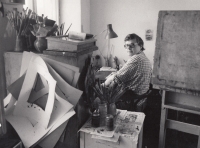

Roman Karpaš was born on October 30, 1951 in Liberec. He graduated from the Faculty of Education at Charles University and in 1973 joined the then newly built primary school in Vrchlického Street in Liberec. After being forced to leave his teaching post, he became the director of the Small Art Hall in the same city. He managed to organize high-quality exhibitions, not burdened by political ideology, and to give space to young artists who were not very well supported at the time. In 1988, he became the art editor of Severočeské nakladatelství. After the liquidation of the publishing house after 1990, he moved to the newly established Dialog publishing house. After the Velvet Revolution, he decided to publish geographical and historical literature free from political censorship. Under his hands, books about Liberec and its surroundings were created, as well as publications on historical postcards. Probably his best-known publication is Kniha o Liberci (The Book on Liberec), first published in 1994.