Don’t refuse anything, don’t push your way anywhere

Download image

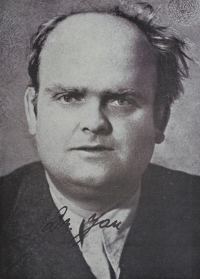

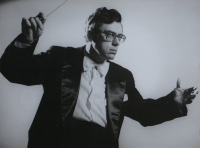

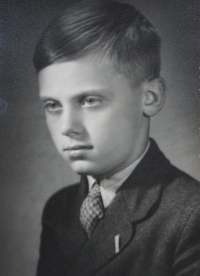

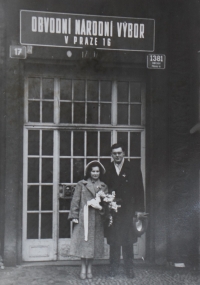

Reginald Kefer was born on 27 July 1936 in Prague. His father, Jan Kefer, became chairman of the Czechoslovak hermetic society Universalia and excelled in astrology and esoteric sciences. Because he refused to cooperate with the Nazis, he was imprisoned in the Flossenbürg concentration camp, where he died in 1941. The witness´s mother died six months after her husband when the burden of a difficult period in her life fell upon her. The orphaned Reginald Kefer lived with his grandparents in Smíchov. There he also experienced the Prague Uprising, when at the age of eight he worked as a liaison for the Vlasov army. After the war, he studied organ at the conservatory. He played regularly in many churches and travelled all over the world to perform. In 1956 he entered the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague, where he studied conducting. He soon gained a reputation in this field as well. He became conductor of the opera in Ústí nad Labem, and also travelled to the State Opera in Dresden. With his wife and children he moved to Brno, where he conducted a radio orchestra. In 1968 he joined the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ) and was involved in the Prague Spring. During the normalisation period he was fired from Czechoslovak Radio. He worked as an assistant in the Brno Philharmonic Orchestra to František Jílek, who was a prominent interpreter of Leoš Janáček’s music. In 1977, he left for Olomouc, where he led the opera theatre. He recruited a number of excellent soloists for it. He refused to sign the so-called Anticharter. He went on to perform in the Czech Republic and abroad, taught and received many important awards. In 2020 he was living in Olomouc and still teaching at the elementary art school.