Everyone should pursue their happiness but at the same time be decent and not allow for persecution of others

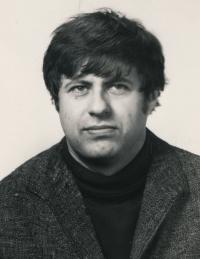

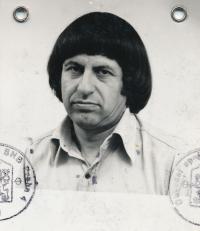

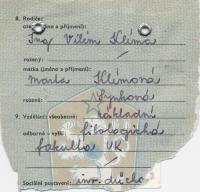

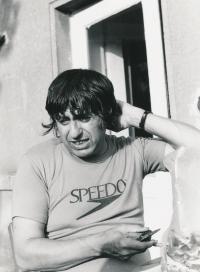

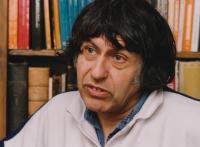

Ivan Klíma, né Ivan Kauders, is a Czech writer, playwright and journalist. He was born on 14 September 1931 in Prague and during WW II spent three and a half years in Terezín concentration camp. Since his father was responsible for all electrical management in the camp, he was spared from transport to any of the extermination camps. After the war he graduated from a grammar school and then spent a semester at the University of Political and Economic Science, later graduating in Czech language and literature from Prague’s Faculty of Arts. He then worked among other things as an editor of the magazine Květy and from 1956 to 1963 in the publishing house Československý spisovatel. He published in Literární noviny, Mladá fronta, Host do domu, Orientace and other periodicals. Between 1963 and 1969 Ivan Klíma served as deputy editor-in-chief of Literární noviny. Already in 1953 he had joined the Communist Party from which he was expelled after an open public criticism presented at the Fourth Writers’ Congress in 1967. He had returned to the Party at the end of the 60s before being expelled for good in 1970. In the following era until the fall of the socialist regime he was only able to publish abroad or in samizdat to which’s emergence and existence he contributed significantly. After the revolution, he was awarded several literary prizes. At present he lives in Prague and still devotes to writing.