Until 1989 everyone lived a kind of inconsistent life. People had to dissemble if they wanted to achieve something professionally of if they didn’t want to go directly to jail. It was a time of daily fear, humiliation, and oppression

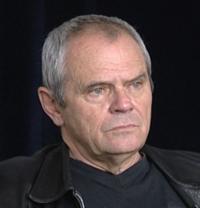

Milan Kňažko was born on August 28, 1945 in Horné Plachtince, in the district of Veľký Krtíš. After graduating from secondary technical school of construction in 1963, he enrolled at the Academy of Performing Arts in Bratislava. As he was not accepted for the study at first, he found a job as a scene-shifter in the Slovak National Theatre. A year later, he began to study at the Theatre Faculty of the Academy of Performing Arts, from which he graduated in 1968. In the years 1968 - 1970 he attended postgraduate studies at the International Theatre Institute in the French city of Nancy. After his return, he worked in Bratislava theatre called Divadlo na korze (Theatre on the Main Street), which was abolished by the political decision in 1971 and affiliated to the theatre Nová scéna (New Scene). In 1985 he was hired by the Slovak National Theatre, where he worked until 1990. Since his childhood he was raised to have a negative attitude towards the communist regime. When he was five, his father was arrested by the State Security, and in a fabricated trial he was sentenced to thirteen years of imprisonment for “espionage and subversion of the socialist state”. When he was only an elementary school student, he used to express his disapproval of the totalitarian power, which had such a hard impact on his closest relatives. He held on this attitude also in his adulthood. In this period Milan Kňažko worked hard on building his acting career. However, he didn’t join the communist party, though in the circles he worked, he was expected to do that immediately. In the period of normalisation, Kňažko became a well-known and popular actor; however, rigid and dogmatic policy of the regime also had a negative impact on culture, which actually intensified his aversion to the republic. His hostility to the regime was fully revealed in 1989, when he signed the petition called Niekoľko viet (Few Phrases), which had been drawn up by the Charter 77 and contained the claim for the civil freedom. Afterwards, his acting career became even more restricted. Due to his disagreement with the policy of the communist regime he even returned his title of Merited Artist in October 1989, though it was an extraordinary act back then. This was one of the incentives that prompted him to participate actively in all the political events of November 1989. He was one of the founders of the Public against Violence movement (VPN), co-organiser and a host of mass meetings held in November in Bratislava and he also became a member of the Coordination Committee of the Public against Violence movement. After the fall of the communist regime in 1989, Milan Kňažko worked as an advisor for the Czechoslovak President Václav Havel in Prague and at the same time he was a member of the Federal Assembly. He remained active in political life. In the years 1990 - 1991 he was a minister without seat and later, he became a Minister of Foreign Affairs. In the years 1992 - 1993 he was a Deputy Prime Minister and a Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Slovak Republic. From March 1993 to October 1998 he worked as a member of the National Council of the Slovak Republic and in the years 1998 - 2002 he held the post of Minister of Culture.