The story of one photo album

Download image

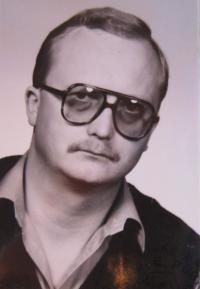

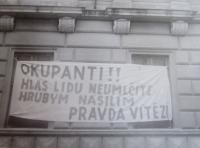

Jaroslav Kočí was born on 8 June 1950 in Šumperk. Both his parents were Viennese Czechs who re-emigrated to Šumperk in 1945. His father had been drafted into compulsory military service in the Austrian army in 1937. However, with the Anschluss in March 1938, Austria had been joined to Nazi Germany. Soldiers of the Austrian army thus automatically became members of the Wehrmacht. Ranked as a private, his father took part in the offensive on Poland. His unit went all the way to the River Bug, which was the demarcation line between the German and Soviet spheres. He carefully documented the whole campaign with his camera, including three photos of the friendly meeting between the two armies. After France fell in 1941, his father requested to be released from the Wehrmacht with the explanation that he did not see himself as a German, but as a Czech. His request was accepted, and until the end of the war he had to serve in the auxiliary units of the Technische Nothilfe. His son Jaroslav Kočí had nothing to do with the dissent or with anyone actively resisting the Communist regime, but even so, on 31 March 1981 the District Court in Šumperk gave him a suspended sentence of eight months in prison for political offence. According to the court, he had supposedly been promoting Fascism merely by showing a few political officials the photographs his father took of the friendly meeting between soldiers of the Red Army and the Wehrmacht at the River Bug in Poland. He had wanted to prove them what is now a well-known fact, that the Communist Soviet Union and Nazi Germany had divided Poland between themselves. The verdict was followed by a dismissal from work and the public scorning of a “promoter of Fascism”. No one wanted to help Jaroslav Kočí clean his name, and so he decided to help himself. A number of coincidences enabled him to apply and be accepted to study law; after graduating he turned to the courts, and in 1994 the High Court in Prague discarded the original ruling as unlawful.