They said a miner without milk won’t live till sixty

Download image

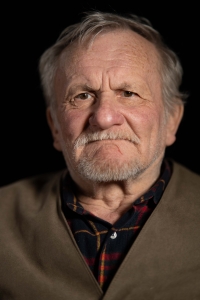

Josef Kocman was born on 16 March 1946 in the Czech village of Eibentál (Eibenthal) in Romanian Banat. His grandfather František died during a coal mine explosion close to the town of Lupeni in 1942. The witness’ father František worked as a miner in the local anthracite mines, married Alžběta Fajglová and brought up three children together. From his childhood the witness helped out in the household farm and when taking the cows out to pasture he enjoyed listening to the stories of the locals, who he also often visited over winter. In the town of his birth, Eibentál, he completed seven classes of school (with a one year break) and later trained as an electrician in the town of Anina. He continued with his profession and in the years of 1964–1996 he was employed at the local mines, where he was offered membership in the Romanian Communist Party. His three-years-younger brother Štěpán also worked in the mines, and died at the age of 64. The witness currently holds the position of local chronicler, enjoys welcoming and telling stories to Czech tourists and is counted among the important native villagers. He is also the author of the book Vyprávění o Banátu – povídání s Jánem (Tales of Banat – talks with Ján) that was published in 2011. At the time of recording he was still living there (October 2021).