If it wasn’t for the good Czechs, the expulsion would’ve been much more painful

Download image

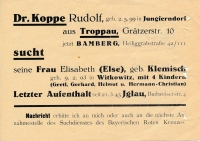

Margarete Koppe was born on 17 July 1928 in Opava to the German family of a financial officer and a piano teacher. Due to her father’s job, she spent her early childhood in Jihlava, but “home” for her is represented by her father’s birthplace of Kobylá nad Vidnavkou (Jungferndorf in German, Jeseník district). The father, Rudolf Koppe, was sent back to Opava in the summer of 1938, on the eve of the Munich Agreement and annex of Sudety to Nazi Germany. Despite the allegedly rather anti-Nazi positions of the father, Margarete was a member of the League of German Girls. In September 1944, their father had to enlist, he was captured in France and his family only met him after the Expulsion. The front was approaching Opava at the end of January and the Koppe family were evacuated from the town. They lived through the end of the war in North Bohemian Staňkovice, where a new Czech priest, father Hroznata, took care of them. Koppe gratefully remembers his humane approach to this day. From the Staňkovice parish, Margarete watched the march of hundreds of Žatec men on foot to Postoloprty, where most of them were subsequently massacred. The weeks before expulsion the Koppe family spent locked up in an empty Žatec, on 13 May 1946 they were expelled in covered cattle cars to Germany. Margarete spent her first years after expulsion in bombed-out Schweinfurt, completed her education and began to work as a teacher. She visited Czechoslovakia for the first time with her father, in 1968, since then she has made regular visits to her previous homeland.