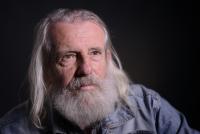

I only escaped criminal charges because of the shoddy work of State Security

Download image

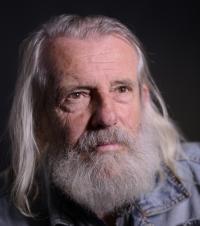

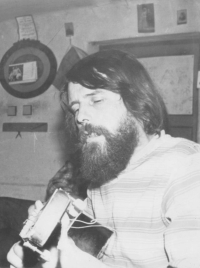

Jiří Kostúr was born on 8 September 1942 in Prague-Jinonice. His mother was Czech and his father Slovak. He learnt to be a lathe-hand in Prague-Vysočany, he worked in the Prague factory of ČKD Sokolovo, but he was fired when he stopped going to school; he then transferred to ČKD Stalingrad. His school of life was spending time in a military prison in Sabinov, Slovakia, where he served a thirteen-month sentence for stealing a car, and later spending time in a civilian prison in Prague-Pankrác, where he spent four months for failing to inform about his and his fellow inmates’ intention to burglar a munitions depot and escape over the borders. After failing entrance exams to the Secondary Vocational School of Art (the “Hollar”), he earned his living as a boilerman, a woodcutter, and a coachman. He also started writing. He moved to the Most District. The relaxed attitudes of Prague Spring enabled him to gain a six-month exit visa to France, where he visited the painter Miloslav Moucha. He earned his living at a sawmill in Alsace. After meeting with Josef Jedlička and Ivan Diviš in Munich, he began copying out Diviš’s poems, which were published in the West. In 1973, editor Josef Volák and writer Miroslav Florian helped him officially publish a collection of scenic poetry Roční doby (Seasons of the Year) in his homeland. He became active in Most (while employed as a co-driver for ČKD Prunéřov and later as a driver for OÚNZ Most) and became acquainted with the underground community in the nearby town of Lom. He soon became one of the twelve co-owners of the estate in Nová Víska. He was also there in 1979 to join František “Čuňas (Porky)” Stárek in the creation of the samizdat magazine Vokno (Windo), for which he wrote articles on culture and ecology and which he helped print. He signed Charter 77 in April 1981. In November of the same year, State Security organised a big raid on the people around Vokno, and the magazine was stopped for some time. Those arrested were: František “Čuňas” Stárek, Miroslav “Šimako” Skalák, and Ivan Martin “Magor (Loony)” Jirous. Although Jiří Kostúr did not have to sacrifice several years of his life because of the magazine, he was deemed an “objectionable person” and was afflicted with numerous interrogations and surveillance, and together with other members of the underground community he was evicted from the estate in Nová Víska in late 1980, and he and his family were also forced to abandon the parish house they were renting in Rejšice. He wrote a collection of short stories about his life, Satori v Praze (Satori in Prague; Pragma, 1993), he summarised his commentary to the extant three-hundred-page dossier of State Security records in his book Dobrý práskač Švejk (The Good Snitch Švejk). Jiří Kostúr died on October, the 24th, 2023.