We saved ourselves by painting everything we could see around us

Download image

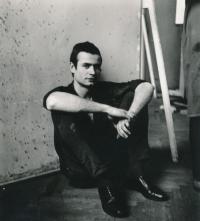

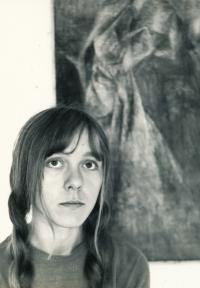

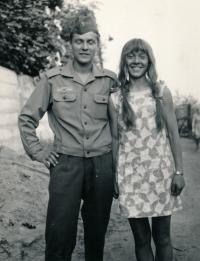

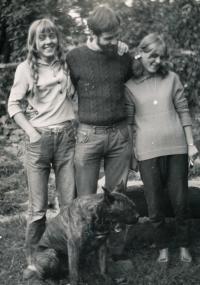

Anežka Kovalová, née Jílková, was born on 1 July 1949 in Šumperk into the family the sculptor Jiří Jílek. She grew up and continues to live in Sobotín near Šumperk, where her parents settled after the war. Her father chaired the local Communist Party cell and founded a visual arts department at the People’s Art School (children’s art school) in Šumperk. In the years 1967-1973 the witness studied painting under Professor Karel Souček at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague. She met her future husband at the university, the graphic artist Miroslav Koval. After graduating she returned to Sobotín, where she collaborated with her father on his art projects until 1981. She avoided politics, she and her husband lived through art. In the years 1980-2013 she taught visual arts at the People’s Art School in Šumperk. When the regime changed in 1989, she and her husband founded the Jiří Jílek Gallery with a permanent exhibition of the work of her father, where they organise authorial exhibitions. The couple raised one son, Štěpán.