I lost my eyesight, but my luck never left me.

Download image

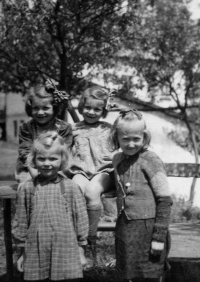

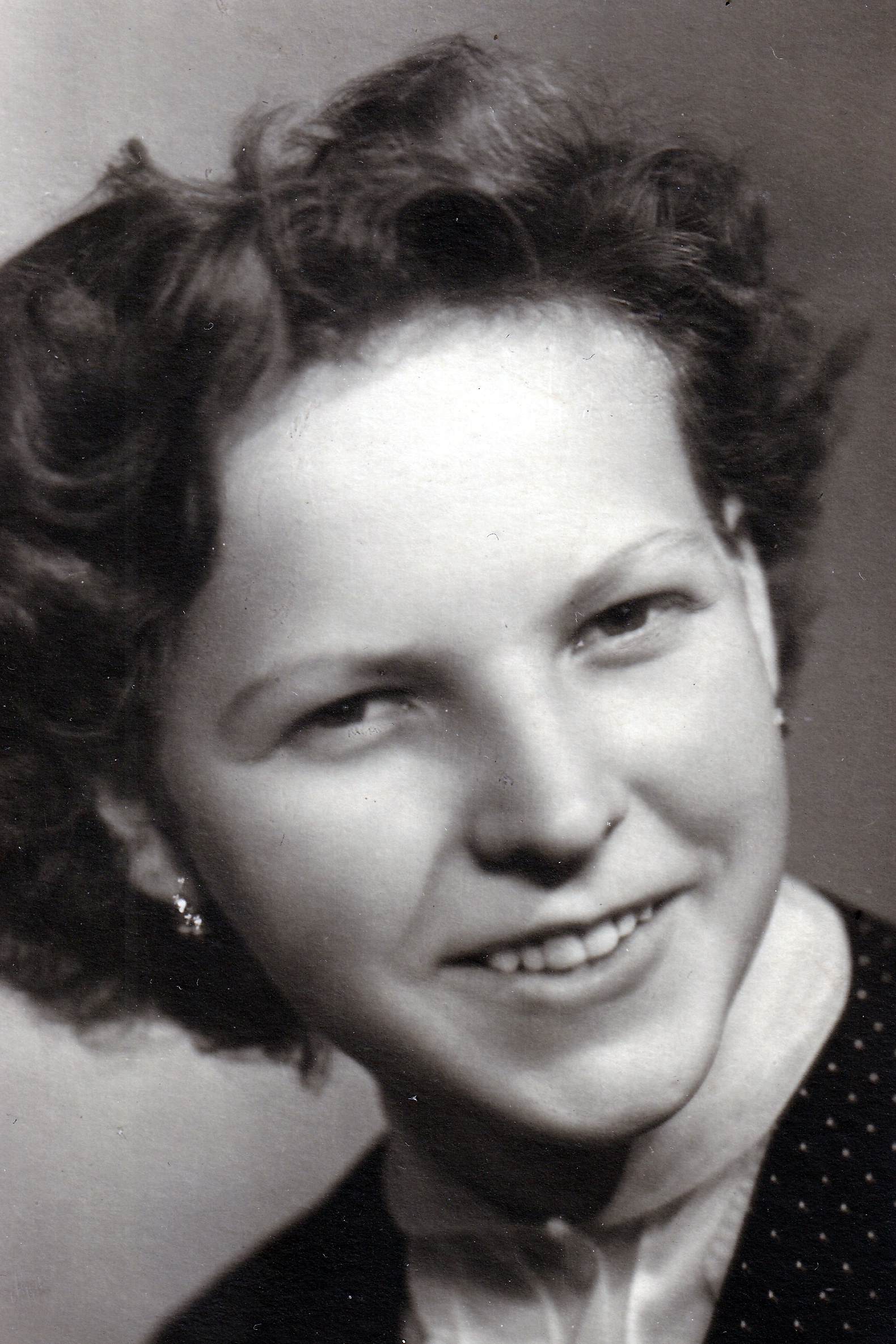

Emilie Kozubíková, née Czudková, was born on 11 November 1940 in Bystřice in what was the German Reich at the time. Her father Karel Czudek was a master baker and ran a bakery and shop in Bystřice. He had to enlist in the Wehrmacht in 1941. He was sent to the Russian front and declared dead in 1943. His mother Marie took over the bakery business in Bystřice. Emilia’s eyesight began to deteriorate at about the age of six. Due to inflammation of the retina, she gradually lost her eyesight. At the age of nineteen, she married Emil Sikora who was also blind. He lost his eyesight in an accident. Two children were born to the couple. Emilie worked as a telephone operator at the Slezan textile company in Frýdek-Místek for thirty years. She was active in the Union of the Disabled, heading the section for the blind and partially sighted. She taught Braille. She wrote several collections of poetry and pieces of fiction. She is a founding member of the Petr Bezruč Literary Club. She lived with her daughter in Frýdek-Místek in 2023.